“I know, for I told me so” – Spinal Tap, ‘The Majesty of Rock’

As part of some recent research I had reason to visit the British Museum’s website, including the pages they provide about the history of their collection and the various departments which manage it – pages like the one for the Department of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas. I soon noticed these pages are presented without references, citations, bibliographies or any other information about the source of the content provided. Even more problematic, particularly when considering citing these pages myself, there is no sign of an author, or even a date of publication. Who wrote this stuff? When?

People are told not to cite Wikipedia for a variety of reasons, one being its perceived reliability; and when the idea of crowd sourcing information for museums, libraries and archives is raised one of the first questions is always about accuracy. Yet if work is cited, sources are provided, and edit histories are visible, a user can readily check the accuracy (or otherwise) of such work. With sites like that of the British Museum, it seems the singular claim to authority is the header of the page which reads ‘The British Museum’.

For another example, compare the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) on Auguste Rodin’s ‘The thinker’ to the Wikipedia page on the work. The former has no author details, no date, and no references, despite making claims about the history and intent of the work, none of which can be verified by simply looking at the work itself. One such claim is that the figure was originally intended to portray Dante. As a reader, we have no idea who made this claim or whether it is accurate.

Wikipedia refers to the same theory, but states that there is doubt about its validity and provides a citation to the work of Rodin scholar Albert Elsen. This not only adds authority to the claim, it also gives the reader the option to follow up the idea if they choose. No doubt the debate is more complex, and one would need to go beyond Elsen to explore it in detail, but it is a start. The NGV, like the British Museum, presents information as fact and seems to expect the reader to accept it as authoritative because it is presented by the National Gallery of Victoria.

There are two problems with this. First, whether we like it or not (and I suspect many institutions, scholars, academics and ‘experts’ don’t like it one little bit) authority no longer works this way. I’m not saying ‘Trust No One’ (despite spending a lot of time with Mulder and Scully in my formative years). But nor should we blindly accept every statement made by a large institution simply because it comes from a large institution. Debate about the meaning, significance and provenance of art works, museum artefacts, archives and published works changes regularly. At least give me a date, a name and a couple of references to go on.

Which brings me to my second point: generosity. The people who wrote pages for the British Museum website and entries about collection items for the National Gallery of Victoria are unlikely to have done so off the top of their head. Even if they did, the knowledge would once have come from other sources – published works, archival documents, conversations with other experts, or similar. Maybe some of the descriptions provided by the NGV present a hypothesis put forward by an art historian, while others are considered historical fact and can be traced through primary and secondary sources.

The author knows which is which. Not sharing this information with the user, not allowing the user to start where they left off and do their own research if they choose, lacks generosity. I have written of the need for generous metadata in the past, and repeat my plea here. Whether working online or off, be generous with what you provide. If you used references, share them. If you have access to detailed metadata, provide it. If you worked through a list of citations, add them to the bottom of your article. And if you are an institution putting pages up on the web and know who wrote those pages and when, then at the very least give me that.

I am a university researcher myself, and an archivist who is always interested in the idea of documentary evidence. That does not mean I’m going to claim the whole web should contain scholarly citations, but it does mean I hold galleries, libraries, archives and museums (the GLAM sector) to a higher standard. We are in the knowledge business. We are professionals, scholars and researchers who believe (I hope) in the value of evidence, the value of a good reference, the value of sharing knowledge with the community, and the value of countering the tendency in other parts of life for people to spout supposed facts based on insubstantial, partial or shoddy sources.

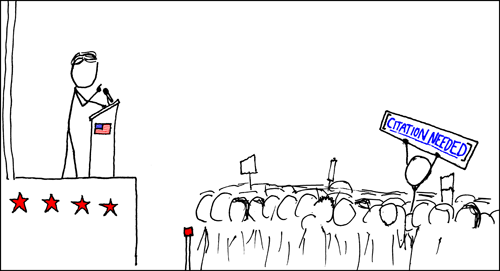

The GLAM sector should be leading by example, not simply publishing text online and expecting the authority of our institutional brands to carry the day. We need to do better; and when we find instances where more is required we need to take our cue from the Wikipedians and ask for a citation.

XKCD, ‘Wikipedian Protester’, https://xkcd.com/285/ (This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.5 License.)

Leave a Reply