In late 1784, London was facing its second severe winter in succession. Frost and snow lay on the ground from early December,[1] reducing access to urban parks and the pleasure gardens at Vauxhall.

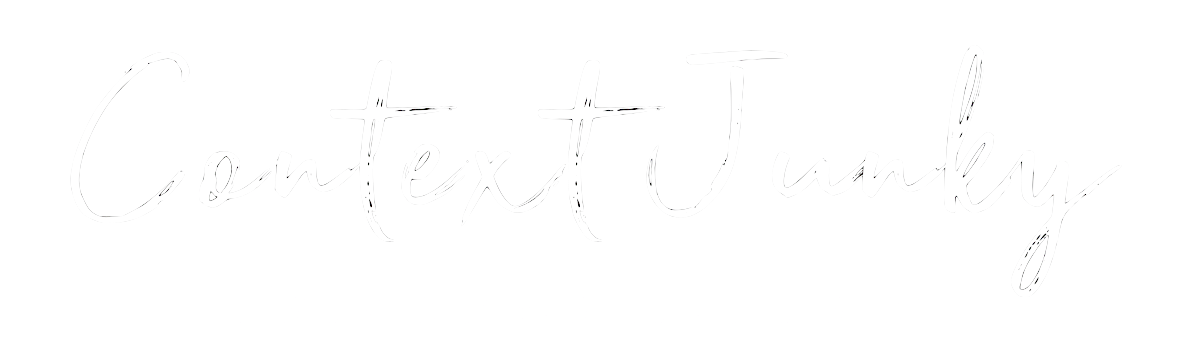

Luckily, Birmingham bookseller and historian William Hutton had hastily arranged a ticket to the British Museum, then at its first home in Montagu House.[2] At 11am on 7 December 1784, Hutton gathered with around ten others waiting in anticipation.

The tour soon got underway; but as their small group was hurried through, Hutton became frustrated and asked their guide if they would be told what they were looking at.

“What! would you have me tell you every thing in the Museum?” the guide replied. “How is it possible? Besides, are not the names written upon many of them?”[3]

Hutton fell silent, only later venting his displeasure:

The history and the object must go together, if one is wanting, the other is of little value. I considered myself in the midst of a rich entertainment, consisting of ten thousand rarities, but, like Tantalus, I could not taste one.

It grieved me to think how much I lost for want of a little information. In about thirty minutes we finished our silent journey through this princely mansion, which would well have taken thirty days. I went out much about as wise as I went in.[4]

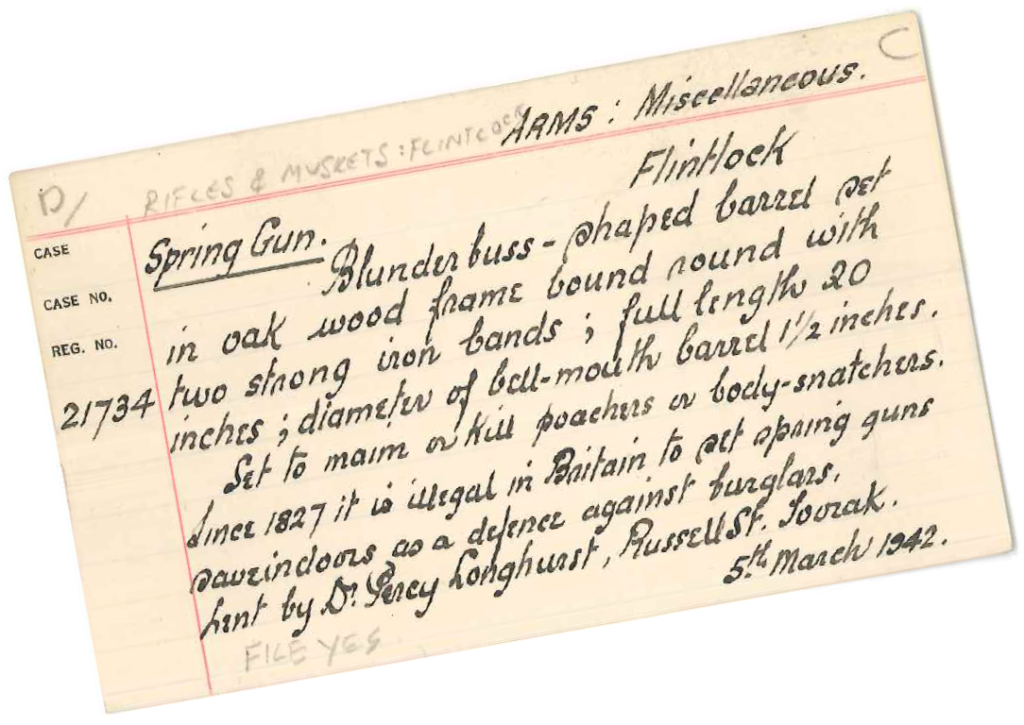

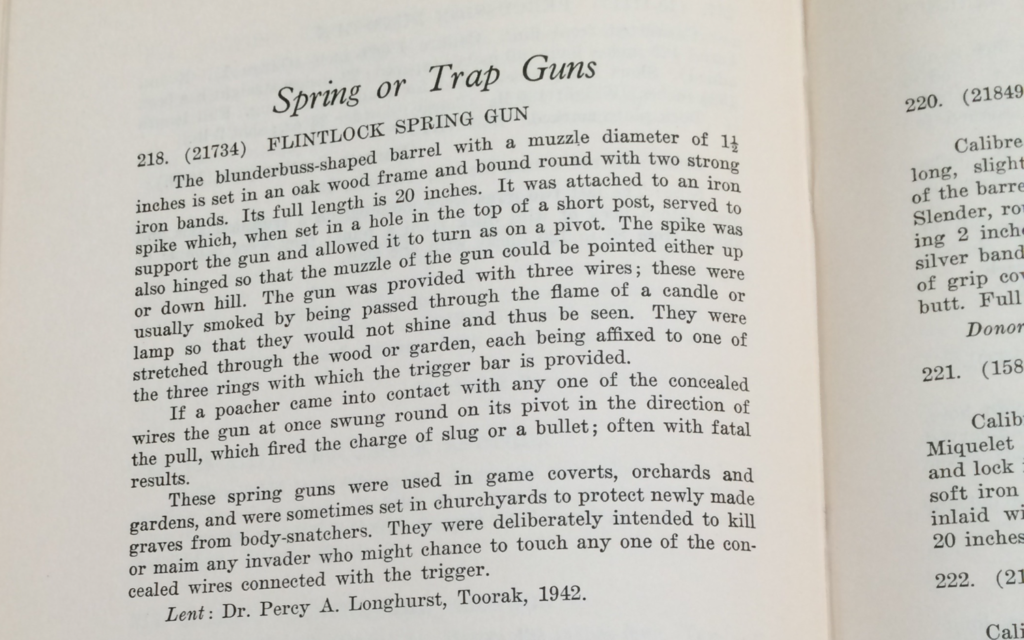

Exhibitions have come a long way since the time of Hutton. There has also been much progress in capturing something of the history of objects, starting with internal technologies like catalogue cards, the scale of which lent themselves to a few basic elements and a concise description. This one (from the Science Museum of Victoria, now part of Museums Victoria) is for a spring gun, a brutal device used to ward off poachers.

Museum catalogue cards were rarely made accessible to the public. Instead, they might refer to something like this descriptive catalogue by Roland Penrose from 1949,[5] which (again in keeping with the format) features a longer, more narrative entry for the same spring gun.

The Penrose entry has another feature in common with much museum documentation I have written about before: a lack of citation. No sources are listed here, despite the fact Penrose lifted his text almost word-for-word from a piece by Miller Christy publised in The Windsor Magazine in 1901.[6]

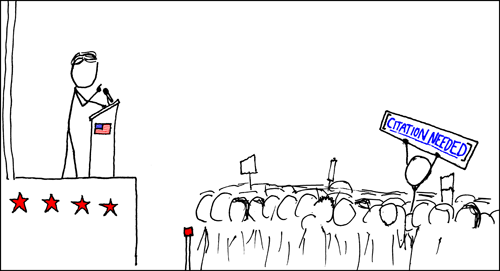

While I am not suggesting widespread plagiarism in museum description, collection management systems traditionally contain large volumes of information presented as authorative, but which any self-respecting Wikipedian would mark with ‘Citation Needed’.

XKCD: Wikipedian Protester

Some exhibition spaces contain contextual or historical displays, like this one at New York’s American Museum of Natural History, which covers the expeditions of Lincoln Ellsworth to the North and South Poles.

As an archivist, I am particularly interested in the use of archival material in historical displays like this. Primary sources like field books provide insights into processes and personalities difficult to obtain from any other source.

Meanwhile, documentation systems have moved on from index cards and published catalogues to computer-aided automation. In 1976, the Science Museum of Victoria made use of a mainframe library cataloguing system run by Swinburne University to produce a microfiche catalogue. Then, following the merger of SMV and the National Museum of Victoria to form the Museum of Victoria, there was Titan; then Texpress, which allowed users to create their own data structures; then a decade-long data cleaning and consolidation process to bring the whole museum into EMu.

These systems are the start of a pipeline that leads to online collections. Claiming that these online collection sites are just the exposure of internal data is an over-simplification. Institutions often work on checking, shaping, and enriching collection descriptions before making them public.

Additionally, there is data that often doesn’t make it into our collection databases. There is technological and conceptual separation that often exists between museum, archival, and library documentation within institutions (which I have examined elsewhere[7]); and there is a whole entangled meshwork[8] of knowledge and context that exists within and around collections which we are not very good at capturing, and which we are even worse at disseminating in a useful way.

Museums have still been a site of significant digital innovation. Take the mARChive collections browser developed by Sarah Kenderdine and the iCinema team at the University of New South Wales, in collaboration with Museums Victoria.[9] The project started by extracting XML from the Museums Victoria collections database, refining and simplifying it due to the numbers of variables in the diverse collections, and the large amounts of narrative text it contained.

There are many digital projects which (though not always as ambitious in their scale and execution) are built on similar foundations. I have seen numerous presentations at Museums and the Web, MuseumNext, and digital humanities conferences, talking about utilising existing collections data. Many are interesting, and some are wonderful. But, at the risk of oversimplifying a whole lot of complex issues, the starting point for digital projects often seems comparable to the rallying cry of Tim Berners-Lee: ‘Raw data now!’[10]

No data is ever raw; and museum data in particular is always cooked.

Decisions are made about what to include and what not to include, with museums rarely including all they know. Projects that then utilise data are not visualising or analysing collections, they are visualising and analysing what institutions have chosen to capture about their collections, shaped by the culture, purpose, technologies, and resource constraints in place, as well as the effect of variations in these over long periods of time. What possibilities could we open up if we used different ingredients and updated recipes before the data was harvested for other purposes?

Here are two quick examples.

The first is a statue from the British Museum. In isolation, we – like Hutton – might ask for more. Add the data that’s available online and we know a little more, but not much. We can use the links provided to fire off some new searches, but little to make us much wiser than when we arrived. A few references to contextual information, publications, or related archival documents would quickly start to open up pathways for exploration.

The second: Museums Victoria holds a significant Children’s Folklore collection, which includes some wonderful documents and photographs, as well as objects related to children’s games and play.[11] Jacks (or knucklebones) were once bones from sheep, but by the 1950s plastic replicas were starting to replace them, particularly in urban schools.

The description for this item is lengthy. There is information about knucklebones in general; two paragraphs about the Dorothy Howard Collection of which this is part; and a physical description. All of this is embedded in an item-level description (with parts of it repeated across numerous other items), making it difficult to process and use in other ways.

What should we do to make our collections data more generous? (I use the term ‘generous’ here with a nod to Mitchell Whitelaw and his idea of ‘generous interfaces’ which he presented at the National Digital Forum in 2011.[12])

If the British Museum example shown earlier is at one end of the scale, institutions like Te Papa – with its rich descriptions, multiple images, and links to contextual material – have taken significant steps toward a better user experience.

The first step is to provide access to knowledge about individual items, as seen with the jacks from Museums Victoria. Many institutions now do this, providing fielded data, narrative text, keywords and other details for individual objects.

A recent illustration by Seema Rao[13] shows some of the information we might look at wrapping around our identified objects. Many online collections sites have started to provide access to at least some of this data, which we can search for and view along with lists or grids of other similarly-wrapped discrete objects.

Then we need to go further. In recent decades, starting in the 1960s and accelerating from the 1980s, disciplines like anthropology, archaeology sociology, and material culture studies have placed increasing emphasis on the interconnected nature of things; on structure, text and context, networks, and entanglement.[14]

Leaving behind essentialist, positivist, and formalist understandings of the world, these works suggest meaning is not inherent to objects, or unchanging regardless of context or time. To describe items in more expansive ways, in connection with their context, we need to look beyond fixed attributes to relationality and the building of identity through interconnection.

Many museums already understand this. From exhibition spaces to catalogues and published research outputs, contemporary museums explore meaning through juxtaposition and context, increasingly stepping over disciplinary boundaries to do so. The recently-opened 200 Treasures exhibition at the Australian Museum is a clear example, explicitly employing the concept of ‘entanglement’ to bring together Indigenous artefacts, natural history specimens, archives, and historical material in a series of ‘tableaux’.

However, it remains rare to find this understanding represented by well-established relational structures in underlying museum documentation, or in collections online sites, even where the knowledge required already exists.

Take the harpoon rope, or kopoi, from Northern Queensland held by Museums Victoria – an item I have talked about before.

It was collected by Donald Thomson, one of Australia’s most significant ethnographic collectors.[15] He collected other material – including other harpoon equipment – from the same area and photographed men hunting dugong in the coastal waters from their canoes. He wrote extensively in the field, his literary estate containing descriptions of his travels, anthropological notes, language, natural history observations, and more. This material has been transcribed and annotated with extensive cross-references, though it is not currently publicly accessible.

Many of Thomson’s artefact and specimen tags also feature names in language and cultural information. Early documentation of the collection captured some of these rich connections; and in-gallery displays at Melbourne Museum include rich cultural information on the myths and traditions related to the emergence of the practice of making dugong ropes from hibiscus fibres (a practice that Thomson also captured in series of photographs).

Though the First Peoples exhibition was based on extensive community consultation, the contents about the rope included in the digital display is closely based on Thomson’s academic article on dugong hunting.

Thomson, Donald F. “The Dugong Hunters of Cape York.” The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 64 (1934): 237–64. https://doi.org/10.2307/2843809.

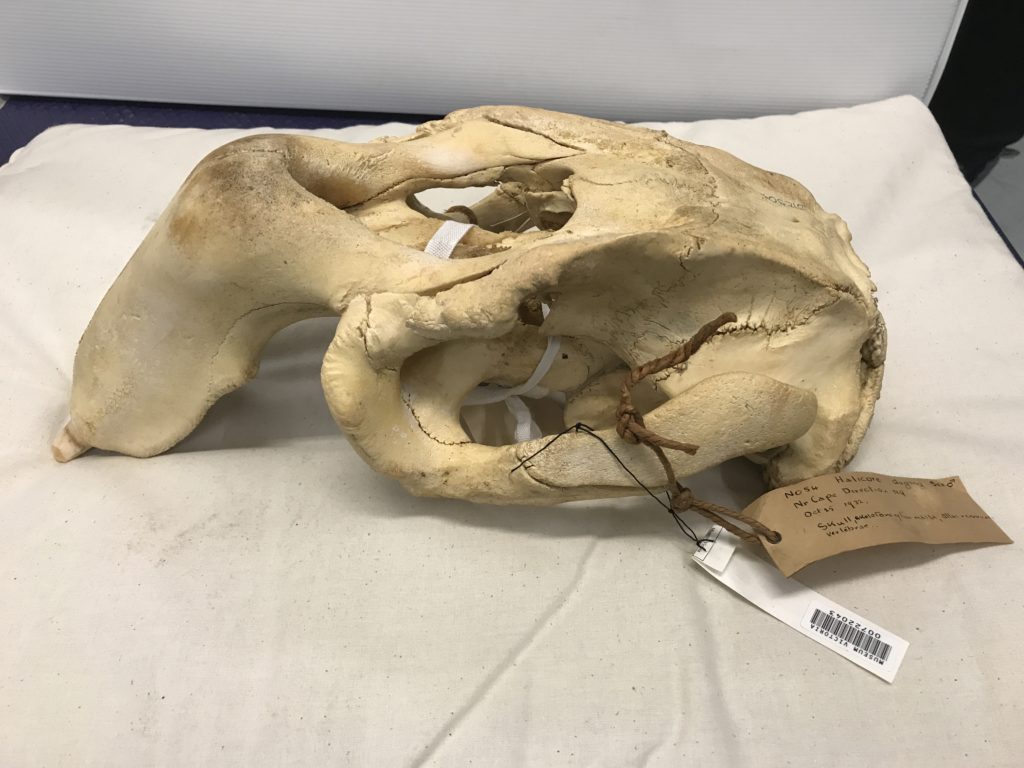

No citation is provided. Thomson also published evocative pieces in the popular press of the time; and, having started as an ornithologist, retained his interest in natural history research, collecting specimens like this beautiful dugong skull.

There is a wealth of content and knowledge available within the museum. I didn’t uncover any of this information for the first time; but only some of this data is captured in relation to the dugong rope in the museum’s collections management system, and only some of that data is available externally via Collections Online and its API.

For people who want to harvest data, for example to explore the possibilities of linked open data,[16] they are getting a subset of a subset of what the institution knows about individual objects, and even less about the known relationships between material. Museums are giving out discrete chunks of information and some beautiful images, while continuing to hold knowledge about their collections – including much of the material that supports their understanding of collectors, communities, and context – closer to their chest.

Rather than duplicating existing work to find that, in fact, the content in the gallery is drawn directly from Thomson’s article, what if we could just follow a citation? Rather than conducting research to re-establish the network that surrounds a single Thomson item what if these relationships were captured, maintained, and accessible as part of collection documentation?

Rather than exploring tens, hundreds, thousands of items via an online collections site and digging through documentation and archives to work out how (or whether) they all fit together, what if people who knew or uncovered such knowledge in our institutions captured it as part of collections documentation? What if our collections documentation systems were more like knowledge management systems, and utilised the network-view of knowledge now prevalent in material culture studies to rethink the information structures we use and the pathways we provide through and between our collections?

What sort of generous collections data would result? And what effect would this have on our ability to build more generous interfaces, engage more effectively with linked open data projects, or produce innovative digital initiatives, whether in our institutions, or online?

In pursuing these ideas, I am not suggesting digital projects using currently accessible collections data are not interesting or useful. Elaine Heumann Gurian has spoken for twenty-five years about the importance of ‘and’ in museums, of pursuing multiple aims simultaneously rather than boiling everything down to a single strategy.[17] Many of the institutions I have looked at and spoken to in the last three years focus on digital innovation while their underlying systems remain based on the information structures and foundational data of the past. Museums need to continue to innovate digitally; and look at capturing more of their knowledge, in more useful ways; and start to think through what the next generation of collections documentation might look like.

Before finishing, I want to look briefly at the Tate, and the combined result of a recent website redevelopment with the documentation work done as part of their Archives & Access project. If we visit the page for an artist, Francis Bacon, we can see an institutional biography, and his Wikipedia entry; and, not surprisingly, we find his artworks.

Scroll down, and we see paintings for which Bacon is the subject – some his own works, some by other artists – and related film and audio. There are links to art historical and thematic narratives featuring Bacon and his work, and primary source material related to Bacon. And there are related art terms, and suggestions for looking further.

Clicking on an archival document, we can view it at page level. As an archivist and art historian I am delighted to find that we can also see where in the archival hierarchy these documents sit, creating a path from the artist, via a letter he wrote, into the broader archive.

The Tate project is not the end goal. Due to the lack of system interoperability, a focus on page level description and digitisation, and the outreach requirements that come with Heritage Lottery Funding, the process used would be prohibitively expensive for many institutions; and there are still a lack of relationships between, for example, individual works and the archival documents that relate to them.

But we are starting to see the development of collection networks here.

To provide more generous data we need to continue down this road. We may need to consider crowd-sourcing, or the implementation of tools which help researchers capture relationships and serendipitous discoveries, as championed by academics like Deb Verhoeven and the HuNI project.[18] We also need to consider the way we capture and manage data gathered about collections when researching exhibitions, or registering new collections. Ideally, over time, we can combine all these things.

Our collections are not just accumulations of discrete objects. They are complex systems that remain connected to a complex world. Rather than grieving, like William Hutton, for lack of information, we need to work to ensure that somehow the vital connection is made.

References

[1] Stephen Hart, “British Weather from 1700 to 1849,” Website of Pascal Bonenfant, 2015, http://www.pascalbonenfant.com/18c/weather.html.

[2] Francesca Hillier, “Montagu House: The First British Museum,” The British Museum Blog (blog), June 23, 2017, https://blog.britishmuseum.org/montagu-house-the-first-british-museum/.

[3] William Hutton, “British Museum,” in A Journey from Birmingham to London (Birmingham: Pearson and Rollason, 1785), 190.

[4] Hutton, 191–92.

[5] Edgar Howard Penrose, Descriptive Catalogue of the Collection of Firearms in the Museum of Applied Science of Victoria (Melbourne: Trustees of the National Museums of Victoria, 1949), 70.

[6] Miller Christy, ‘Man-traps and Spring-Guns,’ The Windsor Magazine, Vol. 13, 1901, from Museum Victoria supplementary file 21734 – Arms – Spring Gun – Flintlock.

[7] See Michael Jones, “Artefacts and Archives: Considering Cross-Collection Contextual Information Networks in Museums,” in Museums & the Web: Selected Papers and Proceedings from Two International Conferences, ed. Nancy Proctor and Rich Cherry (MWA2015: Museums and the Web Asia 2015, Melbourne, Australia: Museums and the Web, 2015), 123–35, http://mwa2015.museumsandtheweb.com/paper/artefacts-and-archives-considering-cross-collection-knowledge-networks-in-museums/; Michael Jones, “Joining the Dots: Building Connections Within GLAM Organizations,” in Collections Care and Stewardship: Innovative Approaches for Museums, ed. Juilee Decker, Innovative Approaches for Museums (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2015), 91–98; Michael Jones, “From Personal to Public: Field Books, Museums, and the Opening of the Archives,” Archives and Records 38, no. 2 (July 3, 2017): 212–27, https://doi.org/10.1080/23257962.2016.1269645; Mike Jones et al., “The Dorothy Howard Collection: Revealing the Structures of Folklore Archives in Museums,” Archives and Manuscripts 45, no. 2 (May 4, 2017): 100–117, https://doi.org/10.1080/01576895.2017.1328695.

[8] Tim Ingold, Lines: A Brief History, Routledge Classics (Taylor and Francis, 2016); Tim Ingold, “Toward an Ecology of Materials,” Annual Review of Anthropology 41, no. 1 (2012): 427–42, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-081309-145920; Carl Knappett, “Networks of Objects, Meshworks of Things,” in Redrawing Anthropology: Materials,Movements, Lines, ed. Tim Ingold, Anthropological Studies of Creativity and Perception (Farnham: Taylor and Francis, 2016), 45–63, http://UNIMELB.eblib.com.au/patron/FullRecord.aspx?p=793207.

[9] Sarah Kenderdine, “mARChive: Sculpting Museum Victoria’s Collections,” in MW2014: Museums and the Web 2014 (MW2014: Museums and the Web 2014, Baltimore, MD: Museums and the Web, 2014), http://mw2014.museumsandtheweb.com/paper/marchive-sculpting-museum-victorias-collections/; Linda Morris, “Digital Cinema Will Allow Visitors to Explore Museum Archives,” The Sydney Morning Herald, September 18, 2014, http://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/art-and-design/digital-cinema-will-allow-visitors-to-explore-museum-archives-20140918-10ebkh.html.

[10] Tim Berners-Lee, “The next Web,” February 2009, https://www.ted.com/talks/tim_berners_lee_on_the_next_web.

[11] See Kate Darian-Smith, June Factor, and Museum Victoria, eds., Child’s Play: Dorothy Howard and the Folklore of Australian Children (Carlton, Vic: Museum Victoria, 2005).

[12] Mitchell Whitelaw, “Generous Interfaces – Rich Websites for Digital Collections,” 2011, https://www.slideshare.net/mtchl/generous-interfaces; see also Mitchell Whitelaw, “Generous Interfaces for Digital Cultural Collections,” Digital Humanities Quarterly 9, no. 1 (2015), http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/9/1/000205/000205.html.

[13] Seema Rao, “Engaging Interpretation (Blog/Graphic),” Brilliant Idea Studio (blog), November 8, 2017, https://brilliantideastudio.com/art-museums/engaging-interpretation/.

[14] There are a whole range of texts in this space. Some of the most influential include: Claude Lévi-Strauss, Totemism (Boston, Mass: Beacon Pr, 1963); James Clifford and George E. Marcus, eds., Writing Culture: The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986); Marilyn Strathern, The Gender of the Gift: Problems with Women and Problems with Society in Melanesia, Studies in Melanesian Anthropology 6 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988); Nicholas Thomas, Entangled Objects: Exchange, Material Culture, and Colonialism in the Pacific (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1991); Bruno Latour, We Have Never Been Modern, trans. Catherine Porter (New York: Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1993); Sarah Byrne et al., eds., Unpacking the Collection: Networks of Material and Social Agency in the Museum, One World Archaeology (New York: Springer, 2011); Ian Hodder, Entangled: An Archaeology of the Relationships between Humans and Things (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012).

[15] Nicolas Peterson et al., eds., Donald Thomson: The Man and Scholar (Canberra: Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia with support from Museum Victoria, 2005); Lindy Allen, “Tons and Tons of Valuable Material: The Donald Thomson Collection,” in The Makers and Making of Indigenous Australian Museum Collections, ed. Nicolas Peterson, Lindy Allen, and Louise Hamby (Carlton, Vic: Melbourne University Publishing, 2008), 387–418.

[16] See, for example, Conal Tuohy, “Bridging the Conceptual Gap: Museum Victoria’s Collections API and the CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model,” Conal Tuohy’s Blog (blog), accessed October 22, 2015, http://conaltuohy.com/blog/bridging-conceptual-gap-api-cidoc-crm/.

[17] Elaine Heumann Gurian, “The Imporance of ‘And’ – A Comment on Excellence and Equity, 1992,” in Civilizing the Museum: The Collected Writings of Elaine Heumann Gurian (London ; New York: Routledge, 2006), 14–18; Elaine Heumann Gurian, “The Importance of And” (MuseumNext, Melbourne, Australia: MuseumNext, 2017), https://www.museumnext.com/insight/the-importance-of-and/.

[18] Deb Verhoeven, “As Luck Would Have It: Serendipity and Solace in Digital Research Infrastructure,” Feminist Media Histories 2, no. 1 (January 1, 2016): 7–28, https://doi.org/10.1525/fmh.2016.2.1.7.

2 Pingbacks