This post comes with a soundtrack. [Or at least, it used to but the link is now broken. Please look up a Terre Thaemlitz track on YouTube, Spotify, or another music service and listen as you read – Mike Jones, 2 February 2017.]

I’m an unabashed music geek with broad, eclectic taste. But I’ve got a bit of a problem with happy music. I like punk, metal and jagged industrial noise. I like some tragedy in my opera, some blues in my rock, and some pain in my soul. I like gospel, but lean toward the brimstone and away from Oh, Happy Day! If you give me country, I want murder ballads or the songs about cheatin’ and your dog running away. If you’re going to sing about love I would prefer it’s lost or unrequited. To paraphrase Sam Cooke’s sublime ode to unhappiness, even when music sounds happy I want it’s smile to look a bit out of place; and if I look closer, I want to be able to trace the tracks of its tears.

That’s one of the reaons I don’t like a lot of dance music, and particularly house. Most of it is too damn happy, too brimming with positivity and forced smiles and joyous party vibes. Terre Thaemlitz (aka DJ Sprinkles) is different. Thaemlitz can be complex, sometimes melancholy, sometimes politically and sonically challenging. You can dance to it, but the sounds, samples, timbres and keys refuse to give you the easy, happy high of mainstream house.

Instead of comforting platitudes, Thaemlitz is interested in context and history. ‘Midtown 120 Intro’ from the masterful Midtown 120 Blues includes the following spoken words:

There must be a hundred records with voice-overs asking, “What is house?” The answer is always some greeting card bullshit about “life, love, happiness…” The House Nation likes to pretend clubs are an oasis from suffering, but suffering is in here with us […] The contexts from which the Deep House sound emerged are forgotten: sexual and gender crises, transgendered sex work, black market hormones, drug and alcohol addiction, loneliness, racism, HIV, ACT-UP, Thompkins Sq. Park, police brutality, queer-bashing, underpayment, unemployment and censorship – all at 120 beats per minute.

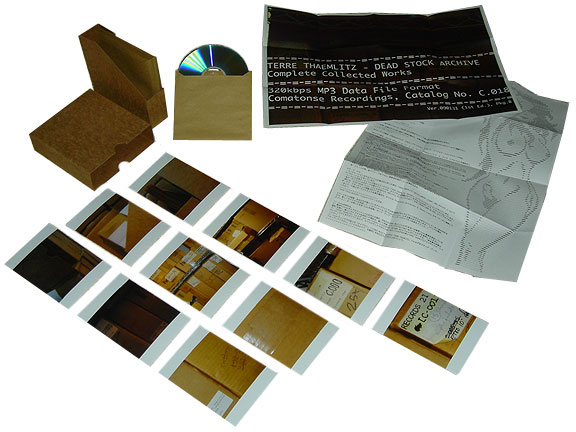

Thaemlitz is also interested in documenting and releasing personal history. On 11 February 2009 Thaemlitz released ‘Dead stock archive‘, a complete ‘collected works’ including 2 DVD-ROM data disks, 8.54GB of audio, HTML/PDF copies of album texts and track annotations, photographs, posters and more in limited edition packaging.

TERRE THAEMLITZ – DEAD STOCK ARCHIVE Complete Collected Works

In an era where artists and record labels regularly trawl the vaults for unreleased versions and alternate takes, Thaemlitz released a completist’s dream: everything in one package. But interestingly (particularly for a DJ) all the tracks are digital versions. No vinyl, no CDs – many (if not all) DJ Sprinkles tracks on these formats remain collectors items.

This gesture reminds me of Marcel Duchamp, who in 1935 started creating ‘portable museums’ containing his life’s work.

Marcel Duchamp, Box in a Valise, 1966, mixed-media assemblage: red leather box containing miniature replicas, photographs, and color reproductions of eighty works by Marcel Duchamp. Purchased through the Mrs. Harvey P. Hood W’18 Fund, the Florence and Lansing Porter Moore 1937 Fund, the Miriam and Sidney Stoneman Acquisitions Fund, and the William S. Rubin Fund; 2011.49. © 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris / Succession Marcel Duchamp

Like Thaemlitz, Duchamp’s ‘complete works’ does not actually contain any of the works themselves. The boxes contain reproductions which represent his earlier works, and which are also themselves original Duchamps.

Duchamp was similarly interested in history and context, referring to the past while also challenging it. He sampled, adding a moustache to the Mona Lisa and tagging her L.H.O.O.Q., which – when spoken in French – sounds like ‘she’s got a hot arse’; and appropriated and remixed objects and images. He ‘queered’ the Mona Lisa with a moustache, and himself by dressing as Rose Sélavy. DJ Sprinkles samples speeches and tracks, started in Manhattan’s transsexual clubs and is a queer activist interested in transgenderism and pansexual Queer sexuality.

Stretching the comparison too far would be a mistake. For example, though Duchamp’s Sélavy challenged convention and propriety ‘she’ is clearly a gesture, clearly Duchamp in drag. Thaemlitz is truly queer, actively problematising and evading traditional notions of gender and sexuality to the extent that different articles about the artist use different gendered pronouns.

But there are similarities, and I’m a fan of both – they are samplers and remixers, iconoclasts and collectors, challenging societal and artistic norms through historically and contextually aware practice.

And though their work is inspiring and uplifting, it’s not disconcertingly happy.

[If you’re interested in finding out more about Thaemlitz’s work, early this year FACT did an excellent feature on ‘The Essential… Terre Thaemlitz‘.]

[On 25 November 2015, the embedded YouTube clip to Midtown 120 Blues was removed from the end of this post as the video was no longer available.]

Leave a Reply