Yesterday I spent the first part of my day at the Royal BC Museum. It is a beautiful place, with wonderful displays and evocative installations throughout. But the highlight for me was the new exhibition Our Living Languages: First Peoples’ Voices in British Columbia which opened on 21 June 2014.

Though not large, Our Living Languages creates a powerful space where the visitor can press buttons to hear greetings in the 34 First Nations languages spoken in British Columbia. There are interactive maps, a video featuring interviews with language speakers and what it means to them, songs, video of a First Nations spelling competition and more.

The experience was also close to overwhelming. I have touched on some of the parallels between our work in Australia and the Canadian experience in a previous post, O Canada, but after my first day encounter with Captain James Cook the Royal BC Museum really brought it home. Cook arrived in British Columbia less than a decade after his arrival on the East coast of Australia, though the British did not formally organise a colony here until the mid-19th century.[1] As with Australia, with white settlement came new industries and technologies, new religions and a gold rush; and with these came disease, oppression and death.

In 1890, 100% of the First Nations population in British Columbia were fluent First Nations speakers. By 2010 the figure was 5.1%.[2] The exhibition noted this figure is now somewhere just over 4%, as older generations of speakers pass away. The primary cause, as with Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islander people in Australia, was the systematic oppression of local culture, language and tradition by white settlers and the attempted forceful assimilation of First Nations people.

One of the primary means for this was the residential school system. As stated on one of the exhibition displays:

To achieve assimilation, the Canadian government worked with churches to create and administer residential schools for First Nations children. Even though the death rate was 40% by 1907, by 1920 attendance was mandatory for children aged 5 to 15. Indian agents and the police forcibly removed children from their homes and arrested parents who resisted. Most residential schools banned Aboriginal languages and punished those who used them.

The last of these “Schools of Sorrow” in British Columbia closed in 1986. (The last one in Canada closed a decade later.) In 2008, the Prime Minister Stephen Harper formally apologised for Canada’s role in the operation of Indian Residential Schools and for the abuse, neglect and disruption suffered by generations of those who attended. But speaking ancestral languages still brings feelings of shame, fear and remorse to some residential school survivors.

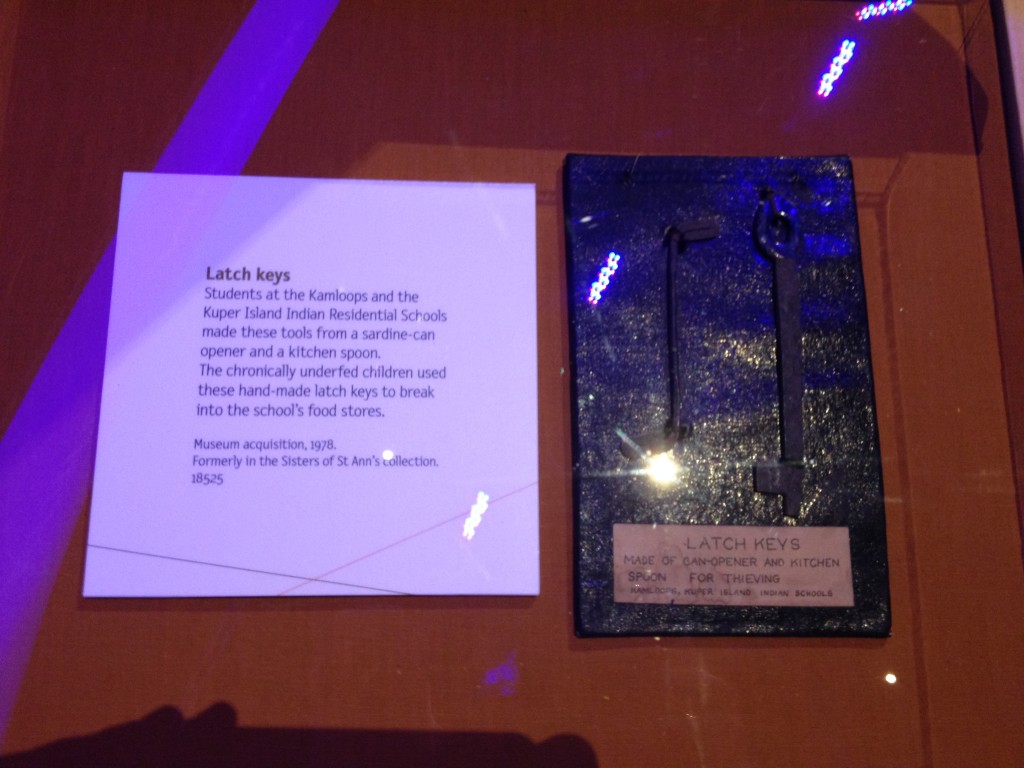

For an Australian in Canada the story is all too familiar, and when encountering these stories – whether they be of First Nations and British Home Children in Canada, or Forgotten Australians, Former Child Migrants and Stolen Generations in Australia – they can have a cumulative effect. Like all good exhibitions, sometimes a single evocative image or piece of text is enough to open the floodgates. Yesterday it was this (apologies for the poor photograph).

Latch Keys, Museum acquisition, 1978. Formerly in the Sisters of St Ann’s collection. 18525. Displayed as part of the Our Living Languages exhibition, Royal BC Museum.

Maybe it was because I was tired, maybe it was just one of those days. Whatever the case, I had to walk away for a while and take a few deep breaths. But though it’s a difficult feeling to deal with, I never want to get to the stage where this doesn’t affect me. These stories are frighteningly common and shockingly recent. We must keep telling them. We must keep collecting and sharing the stories and objects, displaying them in our museums, making them visible to current generations and preserving them for the future. Even – or perhaps especially – when those histories are almost too much to bear.

[1] Wikipedia contributors, “Colony of British Columbia (1858–66),” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Colony_of_British_Columbia_(1858%E2%80%9366)&oldid=602321067 (accessed June 24, 2014).

[2] Report on the Status of B.C. First Nations Languages 2010, First People’s Heritage, Language and Culture Council, Brentwood Bay, B.C., 2010. Accessed online: http://www.fpcc.ca/files/PDF/2010-report-on-the-status-of-bc-first-nations-languages.pdf (accessed 23 June 2014).

June 25, 2014 at 10:14 pm

my sister wept when she went to the NLA general ‘Treasures’ gallery and saw the Indigenous material – evidence of what happened, in physical form. i realised at this point that though i know them to be grave, and heartbreaking, i am so used to these narratives that i’m not moved to tears as she was. exposure does it, i guess, but i want to sometimes unwind it, and listen to a recording of a ‘Stolen Generation’ story as though i had never heard one before at work, and feel it effect me as profoundly as i know it should.

i worked on the Forgotten Australians and Former Child Migrants project – the very initial stages, for the temporary website collating pre-existing collection material before the more intensive search for more stories around Australia began. i trawled the collections for the recordings, and would spend 6 hours a day listening to them. it was one of the most important, and hardest jobs i have ever done. i will never forget those stories.

June 26, 2014 at 2:04 am

Working on the Find & Connect web resource project, where we are documenting the history and records of Forgotten Australians and Former Child Migrant, has been the same for me. One of the most rewarding jobs I’ve done, but often difficult and sometimes heartbreaking.