The following long read is based on my recent keynote presentation at the 2019 Research Applications in Information and Library Studies (RAILS) Conference, Towards Critical Information Research, Education & Practice, hosted by the School of Information Studies at Charles Sturt University (28-29 October 2019).

I acknowledge that we meet today on Ngunnawal and Ngambri country, and pay my respects to elders past, present, and emerging. I am curently working with the Rediscovering the Deep Human Past laureate program and the Research Centre for Deep History at Australian National University (ANU), and continue to be staggered by the scale, depth, and diversity of the history of this continent.

As a white academic with a Scottish mother, and a settler father who started out as a sheep farmer in Tasmania, I don’t speak on behalf of Indigenous communities. Though I refer to ideas from Indigenous academics, writers, and artists in this talk I understand that these do not come close to representing the diversity of language groups, peoples, and perspectives found across Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australia. In extending my welcome to Indigenous colleagues in the room today, I recognise the substantial and ongoing work you do in galleries, libraries, archives, and museums, and in the broader community, to challenge our professions and institutions and change them for the better. But I also believe that the labour required to critically engage with existing practice and effect change should fall to all of us, and it is in that spirit that I am talking to you today.

Until recently I lived and worked in Melbourne, on the lands of the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin Nation. Below is an image of the centre of Melbourne, known as the ‘Hoddle Grid,’ as it appeared in 1855, just after the founding of many large colonial institutions including the University of Melbourne (1853), the State Library of Victoria (1854), and the National Museum of Victoria (1854).

engraved by David Tulloch and James D. Brown (1855)

State Library of Victoria. http://search.slv.vic.gov.au/permalink/f/1cl35st/SLV_VOYAGER786996

The grid carves up and colonises the land, segmenting it into neat, geometric blocks divided by straight thoroughfares named for royals, aristocrats, navigators, and government officials. Elizabeth Street, near the centre of the grid, paves over what was once a creek, flattening the landscape beneath a linear stretch of asphalt lined with imported architectural styles—though nature periodically reasserts itself.

THE AGE Picture by NEVILLE BOWLER, FXJ49866

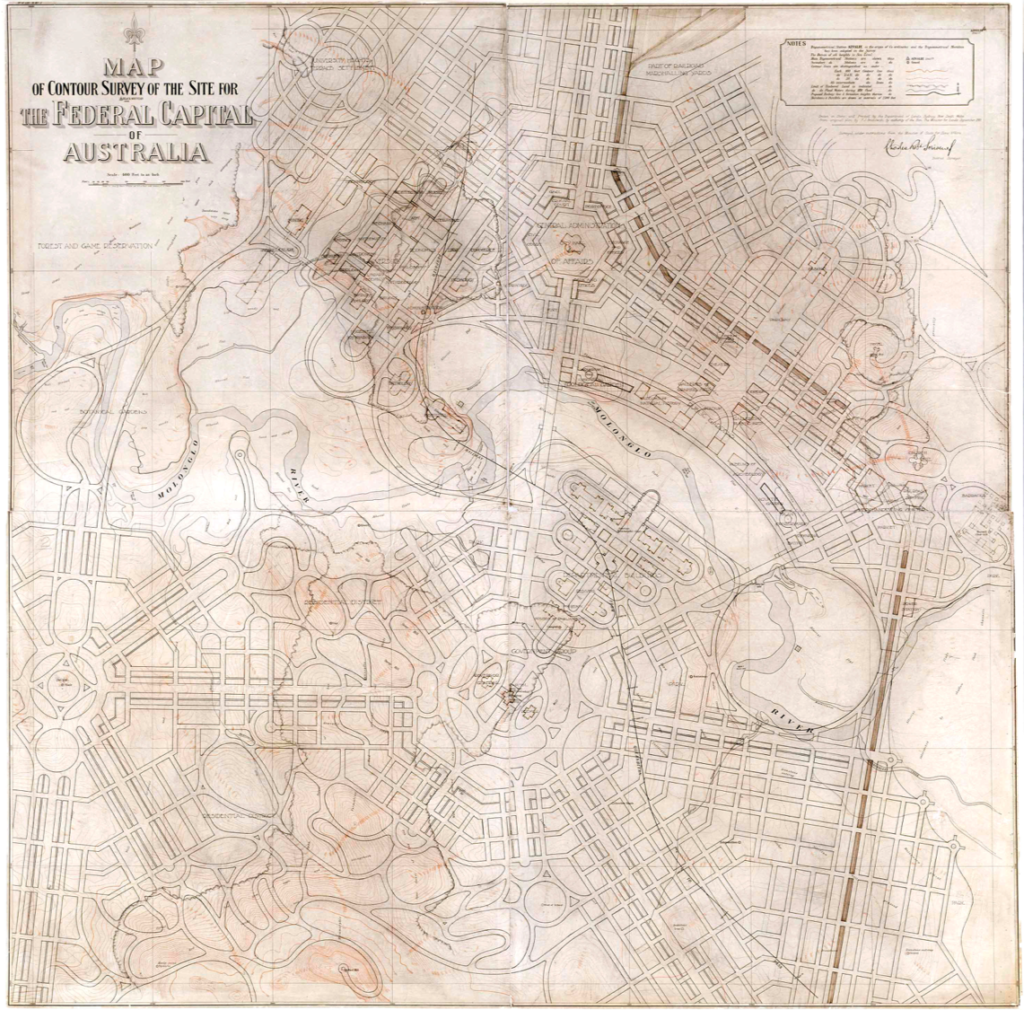

As of mid-2019 I live here in Canberra, at least some of which is the result of Walter Burley Griffin’s plan (drafted by his wife Marion Mahony Griffin) for an ideal city.

I have planned a city that is not like any other in the world. I have planned it not in a way that I expected any government authorities in the world would accept. I have planned an ideal city—a city that meets my ideal of the city of the future.

Walter Burley Griffin

Though the layout is more fluid than a rectangular grid, its hard-edged geometric designs continue to colonise the landscape even while drawing some inspiration from the area’s topography.

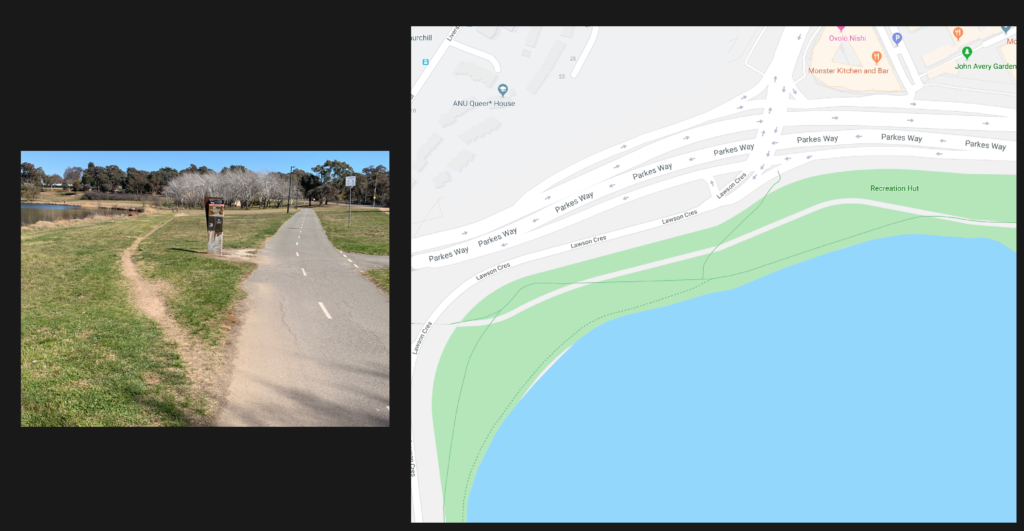

What is more, it seems many pedestrians are keen to step outside the clean lines of one person’s imposed ideal. Desire paths are found throughout the Canberra landscape, more ubiquitous here than perhaps any city I have visited.

Mike Jones (2019).

These paths are found in reserves and parks, crossing empty blocks, and running over the ANU campus where I work. But what is visible by satellite is often missing from Google Maps. The path is an emergent property of the landscape, not one which is planned. When looking at a diagrammatic abstraction of the world this less formal piece of community-generated infrastructure disappears.

Google Maps.

Like all such abstractions, maps conceal as well as represent. Over the centuries visible signs of movement, or reference to the ships, surveyors, journeys, and processes which led to their formation, have gradually disappeared.

the map has slowly disengaged itself from the itineraries that were the condition of its possibility […] the map gradually wins out over these figures; it colonises space; it eliminates little by little the pictural figurations of the practices that produce it

Michel de Certeau

Through this process, constrained perspectives become universalised and selectiveness is treated as objective vision. Wiradjuri author Tara June Winch, referencing Borges in her 2019 novel The Yield, considers the result.

There’s a story I read about someone who wanted to build a map that was the scale 1:1 so that the map covered all the oceans and all the mountains and land at its true size. That made the girls laugh when I told them—imagine walking underneath and holding the thing above your head in the dark? That’s a little what a map does, takes the light out so you can’t see.

Tara june winch

Just as maps mediate our connection with landscape, the registers, spreadsheets, and databases which fill our institutions shape collections-based knowledge. They order, intersect, and dissect it, separating the pieces into disciplines, or cutting them up further into classes and classifications, all the while excluding and concealing other possible groupings and relationships. The processes and people responsible for this work are usually as invisible as the creators of maps, though the work is similarly interpretative. Collection description and documentation shapes our knowledge, privileging certain types of infrastructure, leading us down some pathways while concealing others.

I have written elsewhere on this blog about well-known artefacts like the Gweagal shield, and the ways in which the information captured about such objects decentres Indigenous peoples and knowledges. As Mowgee Wiradjuri man Nathan Sentance writes, the colonial bias of much museum documentation implies:

that First Nations knowledge or culture doesn’t exist until it gets white acknowledgement. That our culture, like our land, needs to be ‘discovered.’ Furthermore, it doesn’t recognise First Nations people as creators of culture and history or as knowledge holders, but rather gives them the roles of subjects

nathan sentance

The connections provided by the formal infrastructure of such records are rigidly colonial. But when we explore collections we navigate through information systems following our own paths.

One such starting point for me was an exhibition I visited at the Cobb+Co Museum in Toowoomba. I confess that my expectation was (perhaps unfairly) that I would encounter an institution dedicated to colonial infrastructure. And there were a lot of carriages. But in the first space I walked into the text panels and object labels were all bilingual, featuring English and Walpiri. The exhibition was about Bush Mechanics, a four-episode television series set in Central Australia, and one of the first shows broadcast where most of the dialogue was in Aboriginal language. For those who have never seen it, here’s episode four, ‘The Rainmakers.’

It features a 1973 Ford Fairlane painted with a ngapa jukurrpa, or ‘water dreaming’, by Thomas Jangala Rice—a beautiful entanglement of temporalities and knowledge systems, of Western technology and Indigenous tradition, of the practical and artistic, of transport and map.

After the exhibition I started to explore further.

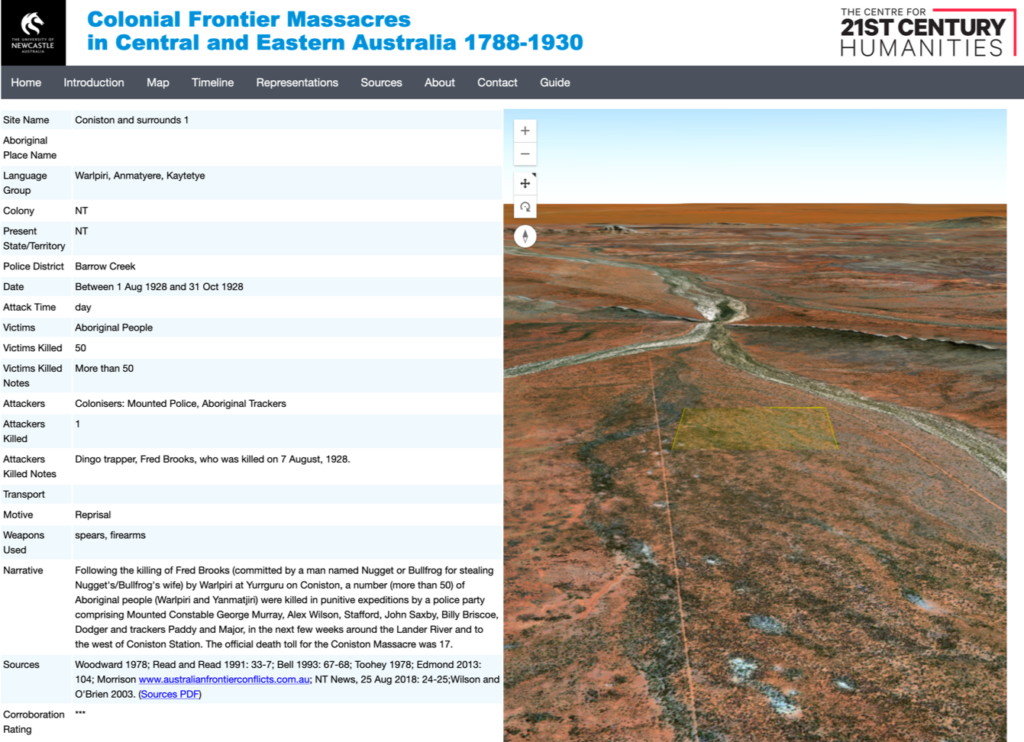

The National Film and Sound Archive includes material related to Bush Mechanics, including photographs of Jack Jakamarra Ross whose stories of his first encounters with Europeans are featured in the show. The National Library of Australia has material produced by Ross, including a set of artworks related to fire and water dreamings. Paradisec includes reference to a Warlpiri dictionary for those interested in language. Trove contains a digitised book by Ross, telling the story of a snake who discovers his partner is being unfaithful. AIATSIS holds a Warlpiri oral history deposited by Ross, who is also featured in a recording about the Coniston massacre. And that event is included on the University of Newcastle’s Massacre Map.

The picture of country featured in this image has interesting visual similarities to another ngapa jukurrpa from 1997, held by the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

Martin, Dolly Nampijinpa Daniels, Judy Nampijinpa Granites, Ruby Nampitjinpa Forest, Rosie Flemming, Jancice Nangala Collins, Maggie Nakamara White, Connie Nakamara White, Joanne Nakamara White, Bessie Nakamarra Sims, Peggy Nakamara White, Ruth Napaltjarri Oldfield, Lucy Napaljarri Kennedy, Maggie Napaljarri Ross, Coral Napangardi Gallagher, Rosie Napangardi Johnson, June Napanangka Granites, Andrea Nungarrayi Martin, Elsie Napanangka Granites, Alice Napanangka Kelly, Thomas Jangala Rice, Darby Jampijinpa Ross, Shorty Jampitjinpa Watson, Jack Jakamarra Ross, Samson Japaltjarri Stewart, Calvin Junggarayi Martin

https://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/collection/works/358.1997/

Among the artists involved in this collaborative work are Jack Jakamarra Ross, and Thomas Jangala Rice who painted the Ford Fairlane featured in Bush Mechanics.

AIATSIS’s catalogue is called ‘Mura’ which is the Ngunnawal word for ‘pathway.’ But there are few visible paths or relationships either within or between any of these distributed catalogues and systems which the user can follow; and, though I have found my own paths through this content, these trails do not remain visible. Nor can I follow the paths of those who have come before me. There are countless potential routes between all these elements. Building more relational infrastructure—a recurring theme in my work—is not just a mechanical exercise in joining the dots. We need to pursue more creative opportunities.

Unfortunately, at the moment that is not always the priority. The GLAM sector (galleries, libraries, archives, and museums) is pushing out more and more collection records and digitised items, from Museums Victoria with more than 100,000 items and 1.1 million specimens online, to the Smithsonian Institution with 14.9 million digital records available through their Collections Search Center. Aggregators accumulate even more content. Europeana has over 57 million artworks, artefacts, books, films, and music. Before removing the collection count from their homepage, Trove boasted of over 457 million.

More is on the way. In her opening keynote at the RAILS2019 conference Director General of the National Library of Australia, Dr Marie-Louise Ayres, spoke about automating some cataloguing and collection description, and outsourcing other work (like archival description) to creators to try and avoid the issue of backlogs.

But do we need larger and larger aggregates with less description attached? Do we need more documentation produced from the perspective of the creator rather than considering subjects, communities, and users? As Michelle Caswell might ask, whose standpoint are we encoding through such an approach, and whose perspectives are being excluded as a result? When aggregating discrete records what pathways and relationships are missing from the map, and what stories, narratives, and connections are being lost? In relying on search technologies rather than rich, contextualised, relational description what are we making hard to find?

Sara Ahmed talks about citation practices as bricks, and cautions that these bricks can be used to form walls as well as shelters. Too often the way we document and describe our collections creates walls of material, tagged with the names of ‘significant figures’ like Melbourne’s Hoddle grid.

These walls not only keep people out, they are also used as a defensive barrier when trying to keep objects in. Tristram Hunt, director of London’s Victoria & Albert Museum, recently wrote of the ‘dangers of decolonisation,’ suggesting that to decolonise is to decontextualize rather than embracing the creative complexity of multi-contextual practice.

Returning to desire paths, their least interesting feature is that they are (at least in many instances) a ’shortcut’. While strictly true, this perspective gives unnecessary primacy to efficiency. Exploring connections (and collections) is not just about getting from A to B as quickly as possible, even if we think we know where B is before we start.

What is more, when considered temporally desire paths are not short, they are long; they take time and iterative action to develop. We need to think about how to embrace temporal, cumulative, community-generated practice in our institutions (including in our documentation systems and online collections), not by surveying users of ‘our’ collections or going out to meet with ‘them,’ but by facilitating, embracing, and learning from the paths that people take (and that people want to take) within and through physical and intellectual spaces.

A key requirement for this is slowing down, rather than constantly trying to build a bigger, faster pipe. Kimberly Christen and Jane Anderson call this ‘slow archives.’

Slowing down creates a necessary space for emphasising how knowledge is produced, circulated, contextualised, and exchanged through a series of relationships. Slowing down is about focusing differently, listening carefully, and acting ethically. It opens the possibility of seeing the intricate web of relationships formed and forged through attention to collaborative curation processes that do not default to normative structures of attribution, access, or scale

Kimberly Christen and Jane Anderson

Moving away from normative structures of access is about creating new paths and opening new doors, not simply widening existing infrastructure and expecting more people to flow through (an idea explored by Nina Simon). As Kirsten Thorpe (Worimi, Port Stephens NSW) argues, we need transformative praxis.

new theory produced by library and archival science professionals needs to draw on multidisciplinary and transdisciplinary perspectives, drawing more thoroughly, for example, on the Social Sciences and Indigenous Studies to understand human experiences, and to create new conceptual and theoretical models that can be utilised to address recurring problems. Without these changes, the profession will continue to privilege certain sections of the population over others

Kirsten thorpe

When thinking about collections, these transformations are about moving beyond the binary critiqued in a recent talk by Jilda Andrews—where ‘source communities’ are seen as coming into contact with ‘destination institutions’—and instead working collaboratively to weave cultural interfaces within and through our institutional practices.

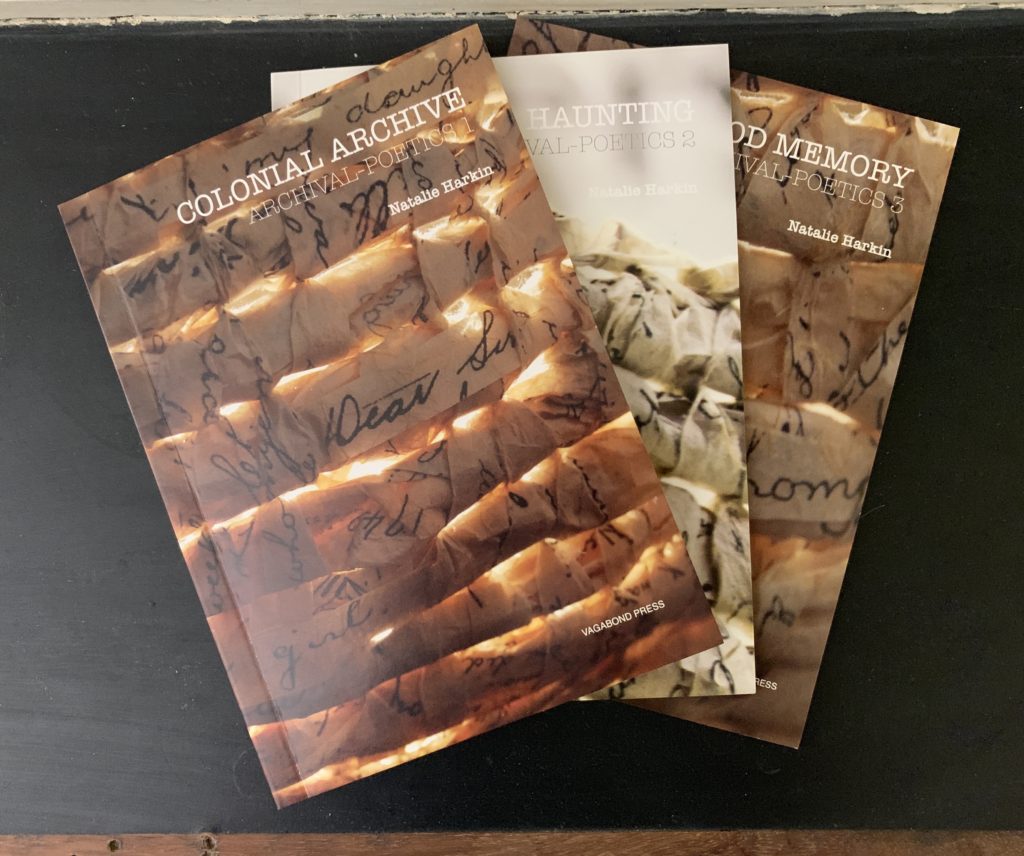

Weaving as a concept is a focal point for many Indigenous modalities. In 2018 the Australian Museum hosted Weave: The Festival of Aboriginal and Pacific Cultures, and within the centrepiece Gadi exhibition South Coast elders Auntie Phyllis and Uncle Steve wove a nawi (canoe) using lamandra reeds. At the Art Gallery of South Australia, the Tarnanthi festival featured a 4.4m long sculpture of a southern right whale woven over seven months by a group of artists led by Aunty Ellen Trevorrow. Artist Natalie Harkin undertakes an ’embodied reckoning with the State’s colonial archive’ in her Archival Poetics, employing weaving in her artistic practice and referencing the concept in her poetry.

Moving away from bigger pipes and seamless efficiencies, we need to focus more on the threads which join things together, and the paths which traverse the spaces between. The word ‘context’ itself comes from the idea of weaving—it weaves things into the world—and context is also the fabric from which people can start to weave alternative worlds out of things, transforming Ahmed’s discrete bricks into strands and strips which produce structure through intersections and overlaps akin to Tim Ingold’s ‘meshworks.’

There are examples available where digital technologies have been employed to focus on relationships, pathways, and the in-between. There is ShipMap where the countries have not been drawn, but emerge through the criss-crossing paths of shipping routes.

Relationships between Facebook friends produce similar results, though in this version of the world countries like China recede into obscurity. In museums and other GLAM institutions there have been experiments with tracking users through gallery spaces. Those who have used Google Analytics will likely have seen the paths people take through websites. And while many desire paths are missing from the apps we use to navigate through the world, Google Maps does capture some of this community-generated infrastructure as dotted lines, like this example running along the side of Lake Burley Griffin.

But all these examples rely on surveillance, large corporations tracking and observing users and landscapes and utilising the results to further develop (and further monetise) their platforms. The equivalent for the GLAM sector would be to track the routes users take through online collections and use the resulting data to provide Amazon-style suggestions, hoping to get people to the thing they want—to the ‘right answer’—more quickly.

That is not what I am advocating here. What we need instead is a ceding of authority and control, moving away from more streamlined dissemination toward a focus on diverse communities and the connections they chose to build up and accumulate. We need spaces where paths emerge over time, and where the connections become indistinguishable from the things being connected. Referring again to Ingold’s work, infrastructure here becomes part of a model of habitation and co-habitation, rather than occupation; of living together within, through, and in relation to the world rather than paving over the top of it like Elizabeth Street paves over that underlying creek.

Our technologies can support this better than they currently do. The web is a problematic model in many ways, its door either a blank search page or an interface placing us at the centre of the world, its connections hyperlinks that whip us from one place to another in as frictionless or seamless a way as possible with little interest in what lies between. Alternative approaches based on visible connections (like those championed by Ted Nelson) have been subsumed by the modern web. Perhaps now is the time to decentre ourselves and repopulate these invisible spaces, to open up our information infrastructure and spend as much time describing and documenting the ‘in-between’ as we do on discrete things, and to open up participatory spaces where others can do the same.

Steps have been taken along this path. Exhibition spaces have started to investigate relational approaches (albeit curated rather than emergent) such as those found in the cascading displays at Sydney’s Australian Museum which bring together groupings of diverse content when items are touched. Mukurtu and Ara Irititja are more participatory, supporting communities in capturing knowledge about collections and developing culturally appropriate access protocols. Meanwhile, research platforms like HuNI allow users and communities to capture, define, and describe their own relationships. Search remains an option, but from this entry point navigation can occur using different approaches. People can follow their interest, explore desire lines left by others, and leave their own relational traces behind when they choose, more interested in journeys and explorations than in arriving at a particular destination.

Relationality also fosters, and is fostered by, different responses to collections. Here is Debora Doxtator talking about emotion.

Can you imagine what it is like to find things in a museum drawer that are somehow connected to you personally? To the museum institution, it’s academia in general. They try to drill into my head that it’s good to be unbiased, that it’s good to separate my emotions and take the emotions out of my work. I can’t. To me, that is false. That’s like pretending that something that is there, isn’t. That’s not good scholarship. To me, that’s closing off a door in my brain that really needs to be open.

deborah Doxtator, ‘The Implications of Canadian Nationalism for Aboriginal Cultural Autonomy’

What if these sorts of relationships—these pathways—were more visibly woven through our systems? What sort of connections might result?

Esther Kirby from the Yulendj (or “knowledge and intelligence”) group at Museums Victoria uses another craft metaphor.

The best way to describe it is one of those patchwork quilts. Everybody’s got a different story and them patches all join together so that you’ve got that overall story. I really appreciate the time that I have when I come down here. I’ve really enjoyed meeting all the museum staff as well. Cause then you’re starting to build up new relationships, new friendships and it just adds to the storyline further down the track. Each person, everyone’s got a story, everybody, not just Aboriginal people.

esther kirby

The Yulendj group brings the cultural interface into the museum, building connections, relationality, and relationships within and through the institution, changing models of authority, curation, and creation. What if all collecting institutions were the same?

Such a shift may be unsettling for some, due to the level of systemic change it requires. In the words of Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, ‘decolonisation is not a metaphor.’ Notions of weaving, connection, and kinship—to knowledge, spirituality, and Country—must go beyond simply tinkering with collection description to improve user experience, increase pageviews, or optimise dwell time. It is about a literal unsettling of existing colonial models and an explicit recognition of the unceded sovereignty of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples over the distributed tangible and intangible heritage in GLAM institutions.

Others might argue that, even with such a recognition, our current catalogues, collections management systems, and processes are still required to impose necessary order on a complex, entangled world; that existing classification systems and hierarchies are still necessary to make our systems and our online collections ‘work’. But to claim this, and to deny the models of authority and privilege established as a result, is to continue to colonise.

Colonialism […] is not the imposition of linearity upon a non-linear world, but the imposition of one kind of line on another. It proceeds first by converting the paths along which life is lived into boundaries in which it is contained

TIM INGOLD, Lines

In this paper, I have proposed that we embrace different sorts of lines and pathways, and more relational approaches, both within GLAM systems and in the ways in which we relate to each other and the world. Change will not be easy, simple, or fast—in fact, it is likely to be difficult, complex, and slow—which is why we must continue to critically engage with practice across the GLAM sector rather than thinking there is only one path. We are all implicated in the results.

Responsibility is learning this country, sharing the stories. Sharing the pain, the hurt. Sharing the untruths.

Who’s responsible? You are. If you call this country home, you are.

Wiradjuri elder, poet and activist Kerry Reed-Gilbert

1 Pingback