This is an edited version of my closing keynote for the Victorian Museums and Galleries Forum on 18 May 2022. The event was hosted by the Australian Museums and Galleries Association (AMaGA) Victoria at Deakin Downtown.

Part I

I would like to acknowledge that we are meeting today on the unceded lands of the Wurundjeri People of the Kulin Nation, and pay my respects to Elders past and present. I would also like to acknowledge and welcome First Nations colleagues joining us in the room and online today.

Though I have spent most of my life in Melbourne, I now live and work on the lands of the Ngunnawal and Ngambri peoples, and am privileged to have an office that looks over their beautiful Country. But, only a few months after moving to Canberra, those lands—like much of Australia’s south east—were blanketed in bushfire smoke. This was the view looking over Lake Burley Griffin to the National Museum of Australia in December 2019.

There were many days like this through December and January 2019-2020. Days when the smoke was so bad the Australian National University (ANU) campus closed due to health concerns, and I would sit wearing a P2 mask in my own living room.

Then came the hail. Hailstones as big as golf balls, ripping down trees, totalling cars, and smashing roofs and skylights. At the Australian Academy of Science staff formed a human chain to move archive boxes in the badly-damaged Shine Dome to a safer location. Campus was closed again. I worked at home for more than a week. The National Museum of Australia closed too, along with many GLAM and other institutions. Some buildings in Canberra are still suffering the consequences of the damage caused on 20 January 2020.

We all know what followed, and the impact it has had on our lives and work, not least for people here in Victoria.

The initial effects of Coronavirus restrictions on the GLAM sector were widespread and significant. Two years ago this month UNESCO released a report on museums around the world in the face of COVID-19. They found that within weeks of a global pandemic being declared 90% of museums had been forced to close their doors for a period of time. By June 2020 it was estimated American museums were losing $33 million per day. I’m sure everyone in this room has seen the effects locally, from thwarted plans and closed exhibitions to budget stress and lost staff, to impacts on mental health and well-being.

Many institutions turned their attention to online offerings. The Wall Street Journal claimed at the time these initiatives pushed museums deeper into the digital age. It’s still not clear how true this is, or whether there will be long-lasting effects on either digital initiatives or audience choices and preferences in the years to come.

Though this presentation will mainly feature Australian, British, and American institutions, it’s worth reminding ourselves that the ‘digital age’ remains very unevenly distributed. For example, UNESCO estimates only 5% of museums in Africa and Small Island Developing States were able to provide digital content. For the remaining 95% when the museum doors closed they were cut off from their communities.

For those institutions with the capacity to produce online content the question remains: if people can access the museum from home (as claimed by the British Museum), and if this museum is always open (as claimed by Museums Victoria), what does this do to physical attendance?

It’s a short step from here to that recurring question: What is a museum? Is it somewhere we can visit without leaving home? If so, does the building need to be there at all? Or is the ‘museum at home’ only a museum at home because there is also a museum not at home? A place we want to access, and perhaps have accessed before, but for which we need a substitute. If so, is it inevitably a temporary substitute? Is it inevitably a poor substitute? We might look at some of the hastily-assembled virtual tours released during the pandemic and say yes. But that doesn’t mean there is not the potential to do something far more interesting, including to produce digital experiences that do things a physical visit can never match.

Current international debates about the definition of ‘the museum’ started several years before the pandemic. Here’s what the International Council of Museums (ICOM) is seeking to replace.

A museum is a non-profit, permanent institution in the service of society and its development, open to the public, which acquires, conserves, researches, communicates and exhibits the tangible and intangible heritage of humanity and its environment for the purposes of education, study and enjoyment.

Again we could ask: when museums closed during the pandemic, were they still ‘open to the public’? In what way were they open, and in what ways were they not open?

Then came this proposed definition, which caused a storm of controversy.

Museums are democratising, inclusive and polyphonic spaces for critical dialogue about the pasts and the futures. Acknowledging and addressing the conflicts and challenges of the present, they hold artefacts and specimens in trust for society, safeguard diverse memories for future generations and guarantee equal rights and equal access to heritage for all people.

Museums are not for profit. They are participatory and transparent, and work in active partnership with and for diverse communities to collect, preserve, research, interpret, exhibit, and enhance understandings of the world, aiming to contribute to human dignity and social justice, global equality and planetary wellbeing.

Interestingly, this could be read as more supportive of the ‘museum from home’ and the types of experiences this offers. But it was a step too far for many. A petition signed by 24 national ICOM committees challenged the text, and the process through which the definition was created. Following a new process we are back down to two possible (and fairly similar) definitions.

Proposal A: A museum is a permanent, not-for-profit institution, accessible to the public and of service to society. It researches, collects, conserves, interprets and exhibits tangible and intangible cultural and natural heritage in a professional, ethical and sustainable manner for education, reflection and enjoyment. It operates and communicates in inclusive, diverse and participatory ways with communities and the public.

Proposal B: A museum is a not-for-profit, permanent institution in the service of society that researches, collects, conserves, interprets and exhibits tangible and intangible heritage. Open to the public, accessible and inclusive, museums foster diversity and sustainability. They operate and communicate ethically, professionally and with the participation of communities, offering varied experiences for education, enjoyment, reflection and knowledge sharing.

These nod to contemporary ideals (that museums are participatory and diverse, with a recognition there are plural ‘communities’ under the banners of the public and society) while coming across as less politically and theoretically adventurous. After the dust has settled, perhaps these are more indicative of where we are as a sector internationally.

The ongoing debate is not just about semantics; it is about people trying to describe the nature of the museum. Nature and nurture are themes running through this talk. Interestingly, in the field of sociobiology it has been recognised that there is often a resurgence of the nature-nurture debate during times of social unrest or at times of crisis. When this happens, there is a tendency to focus on nature—emphasising what are perceived as inherent qualities as a way of explaining people’s place in the world; justifying things by saying that it is their ‘natural place’. Seeking refuge in perceived certainties.

As Freda Salzman writes, focusing on nature in this way is ‘a powerful political weapon, which is used to maintain inequality and to justify our present oppressive social institutions.’

It’s therefore interesting to note, particularly given the stresses of the last few years, how much energy has been expended on trying to define what museums are, as though answering that will help not only explain their place in the world, but justify their existence and value to the powers that be, and (at least in some quarters) justify resistance to change.

To give a brief and very selective tour of some history, the value of collections as a means by which to gain knowledge and understanding about the world has been championed for a long time. Initially this was a largely personal pursuit. Francis Bacon, writing at the end of the sixteenth century, listed the requirements for a modern scholar, including a library; a wonderful garden; collections of animals, birds, and fish; a cabinet of artefacts; and a laboratory.

As we are meeting in Victoria today, it’s worth noting that Frederick McCoy, the influential first Director of the National Museum of Victoria, and one of the four first professors at the University of Melbourne, was an explicit devotee of Bacon’s ideas. He collected a scholarly library, developed the museum and its collections on the University of Melbourne campus (where it remained until his death in 1899), taught subjects including chemistry, zoology, botany, mineralogy, and started a System Garden that remains on the campus to this day.

Bacon’s writings were among the foundational texts for the Enlightenment , which through the 17th and 18th centuries focused on experimentation, observation, and the uncovering of supposedly objective and universal truths about the world. Enlightenment thinking was also inextricably woven through with racist tropes about ‘noble savages,’ and powerful nations mounting expeditions around the globe (including Cook’s Pacific voyage on the HMS Endeavour) that contributed to ongoing colonial expansion.

Some, including my own Vice Chancellor, overlook the problematic aspects of the Enlightenment and continue to champion the value of its ideas. In his annual state of the university address in 2021, ANU’s Professor Brian Schmidt positioned the ‘undermining of the Enlightenment belief in the primacy of the truth’ as ‘the biggest problem in the world today.’ Universities, he argued, are among those institutions with a key role to play in defending truth and democracy.

In addition to universities, by the mid-nineteenth century many large public collecting institutions had formed. Among them the Smithsonian, named for it’s founding donor, Enlightenment-era chemist and mineralogist James Smithson. Here is Joseph Henry speaking about Smithson, in a quote that is carved in the façade of what is now the National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C.

James Smithson was well aware that knowledge should not be viewed as existing in isolated parts, but as a whole, each portion of which throws light on all the other, and that the tendency of all is to improve the human mind, and give it new sources of power and enjoyment … narrow minds think nothing of importance but their own favorite pursuit, but liberal views exclude no branch of science or literature, for they all contribute to sweeten, to adorn, and to embellish life … science is the pursuit above all which impresses us with the capacity of man for intellectual and moral progress and awakens the human intellect to aspiration for a higher condition of humanity.

joseph henry, first secretary of the Smithsonian Institution

Henry’s moralistic tone—similar to that seen in many museums of the time—came with a dose of condescension toward those with ‘narrow minds.’

By the end of the nineteenth century some were starting to write histories of museums, while others—like George Brown Goode (from the Smithsonian again)—were focusing on the future. Goode argued for the role of museums (alongside other institutions) not just as collections of stuff (or a ‘cemetery of bric-a-brac’ in Goode’s memorable phrase) but as key to educating, edifying, and uplifting the masses.

The museum of the past must be set aside, reconstructed, transformed from a cemetery of bric-a-brac into a nursery of living thoughts. The museum of the future must stand side by side with the library and the laboratory, as a part of the teaching equipment of the college and university, and in the great cities co-operate with the public library as one of the principal agencies for the enlightenment of the people.

George Brown Goode, ‘The Museums of the Future’ (1889)

Here we see the institutionalisation of Bacon’s private collections and facilities. There is also a clear hierarchy, with museums as the authorities, as centres of learning and sources of truth, dispensing enlightenment. But these institutions, though claiming to represent universal knowledge, encoded very particular perspectives. Here are the fourteen Secretaries of the Smithsonian, starting with Joseph Henry. Up until the appointment of the current Secretary, Lonnie Bunch, in 2019 see if you can spot what they have in common.

For the bulk of its history, the leaders of the Smithsonian Institution have been male, pale and stale.

(For those interested, this is an album by SF punk trio The Throwups, available via Bandcamp. The lyrics are from their track ‘Thought Leader.’ I think we’ve all met a few thought leaders in our time.)

Though museum leadership in European, American, and Australian institutions remained male, pale and stale for much of the 20th century, other shifts started to occur. One key factor here was money. Comparatively high levels of government funding meant institutions had to be seen to be serving the people; and museums needed to make up funding shortfalls by attracting visitors and extracting revenue from them. Cue blockbuster exhibitions, and a range of other tactics.

There were other shifts too. Marie C. Malaro tracks some of them in her book A Legal Primer on Managing Museum Collections. (If that sounds a little dry, the first couple of chapters in particular are a really interesting read about the nature of museums and to whom they are accountable.)

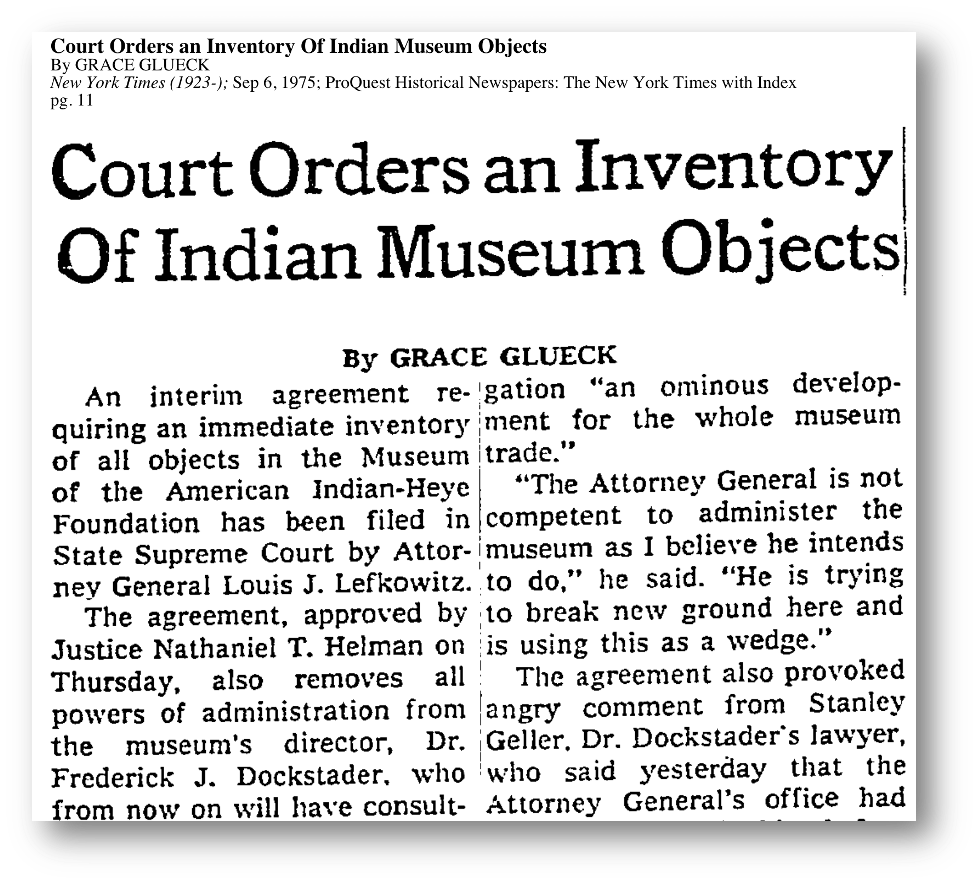

Malaro looks at events in the 1970s, such as the Museum of the American Indian case where: ‘the museum trustees and officers personally were sued by the attorney general of the state of New York for mismanagement.’ Charges included: ‘The trustees and officers failed to keep complete and contemporaneous records of all collection objects […] Essentially, the attorney general of the state of New York was saying that under his interpretation of the law, a museum, as a charitable corporation, has certain obligations to members of the public (as the beneficiaries).’

For those, like me, who are interested in the history of cataloguing and computerisation the court also ordered that an inventory be prepared of the whole museum collection so people could actually see what the institution held, and track any exchanges, gifts, or deaccessions—a concept some characterised as ‘an ominous development for the whole museum trade.’

Together these, and other social and cultural changes, produced a broader shift—or, perhaps more accurately, a flip—traced by Stephen Weil in his 1997 lecture ‘The Museum and the public,’ from the authoritive institution dispensing wisdom to enlighten the populace, to museums as institutions beholden to the public—what Weil characterises as a shift from mastery to service.

We can see this idea today, reflected in all the ICOM definitions shown earlier. Museums are ‘in the service of society,’ they ‘hold artefacts and specimens in trust for society,’ they are ‘of service to society,’ they work ‘in the service of society.’

But this is just replacing one hierarchy with another. When thinking about where we are now, and where to next, I want to move away from hierarchies and binary power dynamics to think about different structures and ways of working.

I want to draw out other possibilities from the long, and the recent, history of museums. Emphasise the fact that Bacon and Smithson (via Henry) were interested in cross-disciplinary connections and the relational nature of knowledge, more than distinct objects, collections, or disciplines. And Goode, leaving aside his moralistic desire for a more ‘enlightened’ populace, was interested in museums as nurseries of ‘living thoughts.’

We can combine this with social and cultural change driven by civil and Indigenous rights movements, and feminist and LGBTIQA+ activism; theoretical developments in museology, anthropology, and related disciplines; and broader shifts in the social sciences away from modernist and classificatory modes of thought toward an interest in networks, relationships, and interconnection.

Here’s an example from Bruno Latour which seems particularly apt in current times.

The smallest AIDS virus takes you from sex to the unconscious, then to Africa, tissue cultures, DNA and San Francisco, but the analysts, thinkers, journalists and decision-makers will slice the delicate network traced by the virus for you into tidy compartments where you will find only science, only economy, only social phenomena, only local news, only sentiment, only sex.

Bruno Latour, We Have Never Been Modern, trans. Catherine Porter (New York: Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1993).

Think of the pandemic, its emergence, and its impacts, all of which belie any attempt to separate humans and the natural world, one geographic region from another, or science from society and culture. If we are not careful, the way we work—the way we document, manage, and exhibit our collections; the way we structure our institutions; the policies we develop and enact—can slice up these delicate networks in ways that are difficult to repair.

Together these interconnected trends help us understand the gradual emergence of different sets of priorities in museums. Some, like Duncan Grewcock, apply the term ‘the relational museum’ to describe this re-imagining of collecting institutions as ‘connected, plural, distributed, multi-vocal, affective, material, embodied, experiential, political, performative and participatory.’

We see traces of this idea in the text of the previous, most controversial definition proposed by ICOM, particularly in its reference to ‘polyphonic spaces’. And we see elements of it in the AMaGA assertion that ‘Australian cultural life is a dynamic ecosystem.’ The idea that this ecosystem includes museums, botanic and zoological gardens, research centres, and more is one that has a recognisable lineage back at least as far as Francis Bacon.

Relationships, ecosystems, community engagement—these elements require nurturing. And it’s here I think the future of museums lies—not through recourse to the ‘nature’ of museums or trying to define a fixed role in society, but in focusing more on developing and nurturing relationships, and fostering new forms of accountability through specific relationships. Some museums have started to do this work, but as we emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic there is now an opportunity to do much more.

Part II

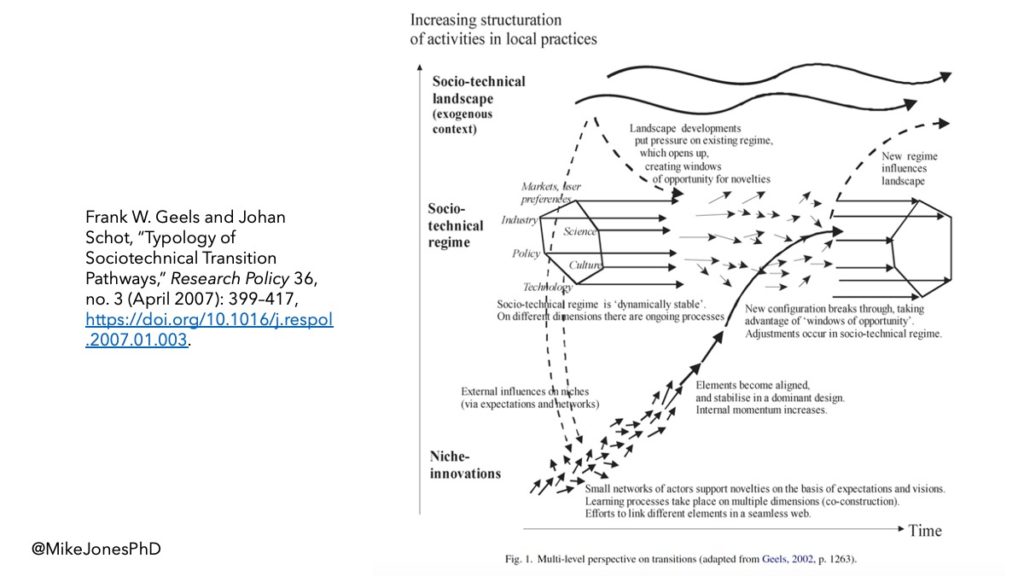

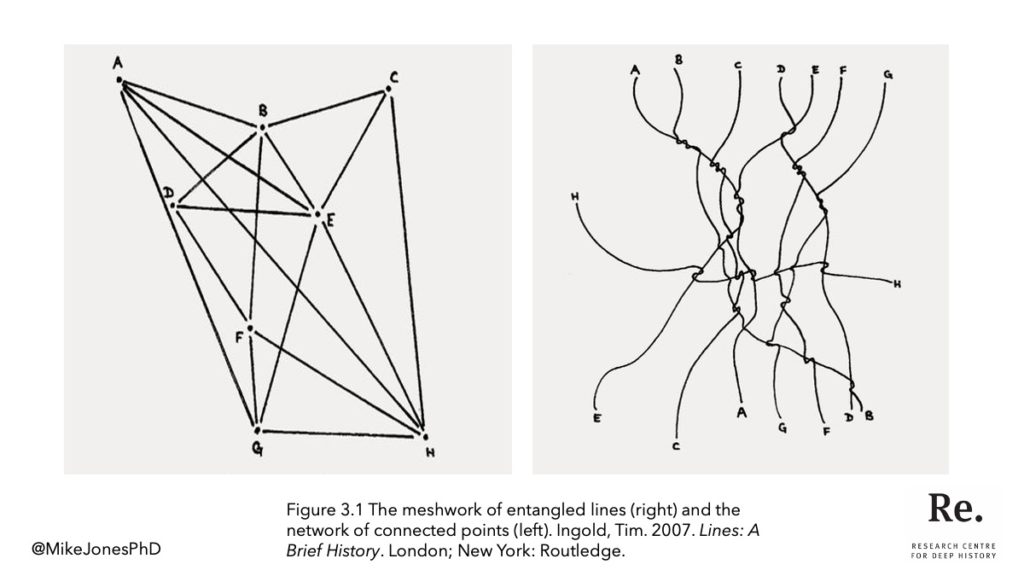

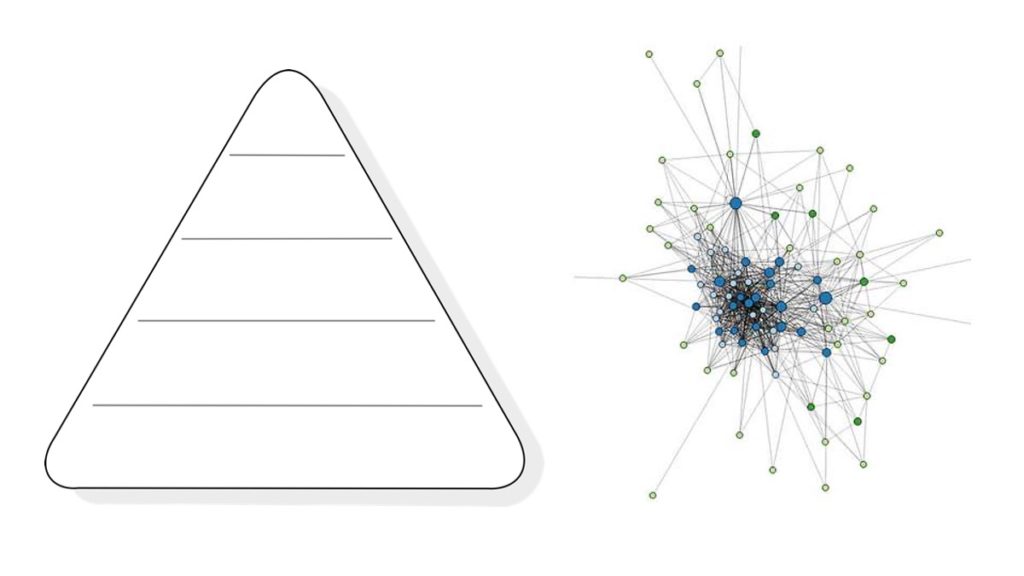

I want to start the second part of this presentation with an unnecessarily complicated diagram.

Please ignore most of the language used here, which isn’t relevant to the overall point. What this shows is three levels. At the top, the overall landscape in which people work; in the middle, the policies, technologies, markets, cultures, and other regimes that structure and constrain the way we work; and at the bottom, small networks of actors creating innovations, and trying to connect these up to produce something larger and more long lasting.

When the landscape develops and changes, it puts pressures on the policies, technologies, and structures we work with, which makes these more open to change. It creates what this diagram calls ‘windows of opportunity.’ Aligning some of the emerging ideas from below, these can then be incorporated into and change the regimes that shape our work, which can then contribute to changing the overall landscape.

Our landscape has undergone a massive shift in the past few years. Natural disasters, pandemics, political upheavals, and more—these have put the structures that shape our work under immense pressure, disrupting them to a greater extent than people have seen for generations.

It’s also produced feelings of isolation; separated people from communities, families, and friends; placed pressure on our physical and mental health; and prompted many people to reconsider what is most important in work, and in life. What relationships are important to us?

As we rebuild and reconnect, new ecosystems and social structures can emerge. New ways of working. Adrienne Maree Brown emphasises critical connections, or critical relationships, rather than critical mass; and the value of small actions.

Emergence emphasizes critical connections over critical mass, building authentic relationships […] emergence notices the way small actions and connections create complex systems, patterns that become ecosystems and societies

Adrienne Maree Brown, Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds (Chico, CA: AK Press, 2017).

Collectively these small actions can produce ecosystems, which in turn can foster different sorts of communities and societies.

In talking about connections or relationships here, I want to think about them in a particular way. Not as a line connecting two pre-existing things with fixed natures, like a link between two static web pages. Not a stable, carefully-defined ‘Museum’ deciding to link up with a ‘First Nations community’, or with refugees, or with trans youth. But of relationships as a precondition for what follows.

Nurturing particular relationships (and not nurturing others) will result in the emergence of particular sorts of museums. The relationships come first, and museums are shaped by them. Where A and B meet, something different is created; both are changed by the encounter.

Relational thinking also provides a different perspective on the ‘truth’—moving away from Enlightenment notions of truth a something fixed, objective, singular, universal—as outlined here by Indigenous scholar Shawn Wilson.

In an Indigenous ontology there may be multiple realities, as in the constructivist research paradigm. The difference is that, rather than the truth being something that is ‘out there’ or external, reality is in the relationship that one has with the truth. Thus an object or thing is not as important as one’s relationship to it

Shawn Wilson, Research Is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods (Black Point, N.S: Fernwood Pub, 2008).

And it means moving away from ‘us’ (inside the museum) connecting with ‘them’ (outside the museum) to nurture internal as well as external change.

For many decades feminist thinking has also emphasised the value of relationships. One influential idea has been the notion of an ‘ethics of care.’

Take Carol Gilligan’s work on the Heinz Dilemma, used by Lawrence Kohlberg to explore moral and ethical development. In the interests of time I’ll explain this quickly: Heinz’s wife is sick with a rare disease; a large drug company has created a drug that can help, but it’s very expensive; and Heinz can’t raise the money. Should he steal the drug to save his wife?

The intention behind the example is for people to quickly turn to abstract concepts—is a human life worth more than property? should we break the law on moral grounds?—to decide from three options: Heinz shouldn’t steal because it breaks the law; Heinz should steal to save his wife, but should be punished by the law; or Heinz can steal the drug and the law shouldn’t punish him. These are labelled pre-conventional, conventional, and post-conventional moral thinking.

At the highest stage of moral thinking, according to Kohlberg, individuals should develop a deeply held set of moral principles that they wish to apply equally to all people, and should apply these even if they run contrary to the law and social practices of the time.

In her 1982 book In A Different Voice, Carol Gilligan questions this, and argues that valid alternative responses—particularly those from young women—are discounted by Kohlberg’s analysis. She gives examples where people have responded by considering Heinz’s relationship with his wife; whether his spending time in jail would cause more problems in the long run; whether she might need more medicine in the future, requiring a more sustainable option than theft; and whether the relationship with the drug provider could be fostered in a way that makes stealing unnecessary.

These participants look at the dilemma and do not see opponents in a contest over rights, but members of a network of relationships that extend through time. Where the dilemma is often stated as ‘should Heinz steal or not steal?’ with the stealing assumed, participants who focus on relationships don’t take this for granted, and try to find a way to nurture relationships in a way that opens up other options.

As Gilligan writes, where one sees ‘a conflict between life and property that can be resolved by logical deduction,’ the other sees ‘a fracture of human relationship that must be mended with its own thread.’

Here are Gilligan’s stages in the ethics of care, from pre-conventional, to conventional, to post-conventional.

- Pre-conventional stage: people are focused on the self.

- Conventional stage: people have come to focus on their responsibilities towards others.

- Post-conventional stage: people have learned to see themselves and others as interdependent.

It could be argued her post-conventional stage is, when viewed through many Western societies and modes of thinking, quite distinct from many dominant socio-cultural and legal mores, not least in its move beyond individualism.

Nevertheless, it’s possible to see a correlation here with early museums, focused on themselves, the interests of their staff, the knowledge they contained, and the authority they embodied; followed by a stage where museums came to focus on their responsibilities towards others—the ‘service’ model I outlined earlier. We are perhaps only just starting to enter the next phase, where museums learn to see themselves and others as interdependent; as entangled in complex ways that require nurturing (and sometimes mending) over time.

These ideas align in many ways with First Nations concepts of the ethical importance of relationships.

An Indigenous axiology [study of value and things that have value] is built upon the concept of relational accountability. Right or wrong; validity; statistically significant; worthy or unworthy: value judgements loose their meaning. What is more important and meaningful is fulfilling a role and obligations in the research relationship—that is, being accountable to your relations.

Shawn Wilson, Research Is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods (Black Point, N.S: Fernwood Pub, 2008).

Those of us working in the GLAM sector need to ask ourselves similar questions: what relationships matter? What relationships do we want to be accountable to?

I want to finish by returning to look at parts of the current landscape through the lens of the concepts outlined above. For example, we can look at the controversy surrounding ICOM’s museum definition and think about the idea of people reverting to an emphasis on ‘nature’ to shore up existing systems of privilege and existing hierarchies.

Take museologist François Mairesse: ‘A definition is a simple and precise sentence characterising an object,’ he said. ‘It would be hard for most French museums—starting with the Louvre—to correspond to this definition, considering themselves as “polyphonic spaces”. The ramifications could be serious.’ Rather than nuturing polyphonic spaces and new ways of working, there is a rejection of this (admittedly aspirational) idea because long-standing museums like the Louvre don’t already correspond. It is not in their nature. But what relationships do we exclude if we universalise a model like the Louvre across all museums? What possibilities do we reject if we argue that we cannot aspire to be something other than what we already are? What are the ramifications of not changing?

There are continuing discussions about repatriation, involving large museums like the Victoria & Albert and its director Tristram Hunt who has argued against the return of looted artefacts. But in doing so Hunt and others like him fall back on an argument about the nature of museums (as world institutions, places for preservation, sites of knowledge) rather than considering what relationships these institutions might want to build and nurture.

Hunt and others like him also rely on a particular ethical framework. This is most evident in the ‘slippery slope’ argument, where directors and others throw their arms up and say ‘if we repatriate items from our collection, our museums will be empty!’ This fallacious logic aligns with Kohlberg’s stages, where the ‘highest’ form of ethics calls for people to decide on a course of action and then seek to apply it in response to every request.

It does not align with an ‘ethics of care’ approach that considers the networks of relationships involved, the actions most appropriate for those relationships, and the impact of our decisions on existing and future relationships through time. As Australian museums increasingly know, when viewed through a relational framework sensitive to context and circumstance, the answer to the question ‘what should happen to contested objects in our collections?’ is still sometimes repatriation; but this is far from universal and many valuable opportunities will be missed if that is the only action under consideration.

If anything, the situation in the UK has deteriorated even further in the last couple of years, and not just because of Brexit. There is a culture war happening with museums, and their ‘service to the public’ (and the public funds attached) is being wielded as a political weapon by politicians like Culture Secretary Oliver Dowden who are loudly telling museums they should be less political.

In Australia there have been attempts to restart a fresh round of culture wars about ‘negative’ and ‘woke’ history by former minister Alan Tudge; fabricated controversies around gender and trans women in sport; and only slighty more sophisticated contributions from former minister Paul Fletcher who spent a few hundred words ‘bothsidesing’ the arrival of Cook and the subsequent invasion of First Nations lands. Rather than ‘polyvocal practice’ here we see that age-old conservative trope: ‘there are opinions on both sides that are equally valid.’

The political landscape therefore provides little support for museums. If further evidence were needed, Australia has just come through an election campaign where only the Labor party released an arts policy, which was light on detail and released at the tail-end of the campaign. More broadly, Labor had no mentions of museums or heritage anywhere in their policy platform; and the Liberal party noted a couple of museums in its section on ‘Tourism’ but little else.

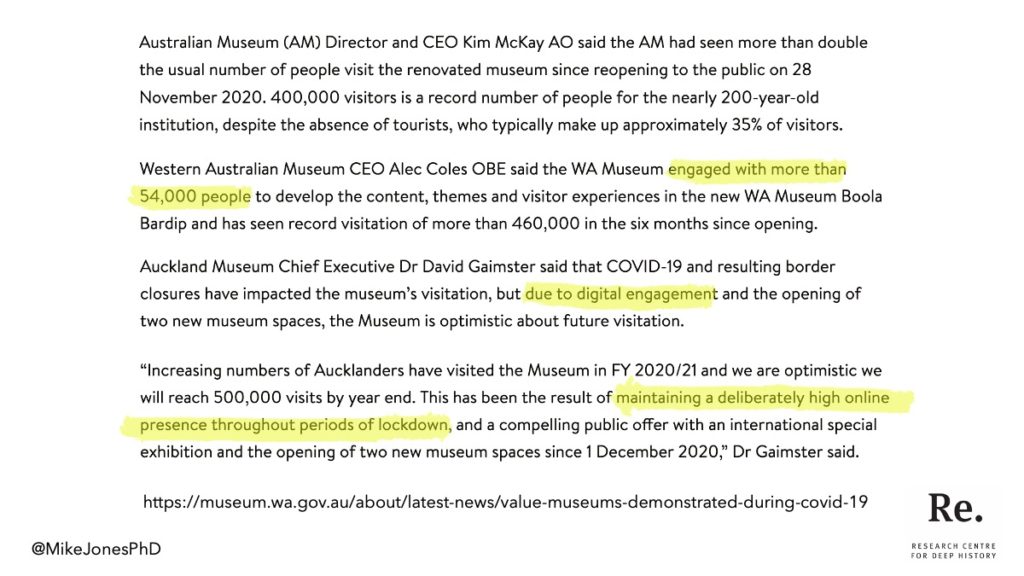

Funding aside, do we want to be accountable to these politicians? Museums are still seen as largely trustworthy by the broader community. More so than universities, far more than politicians, and streets ahead of mainstream and social media outlets. Institutions know that these relationships are vitally important. That’s one of the acknowledged reasons behind all those digital initiatives during COVID—not just to provide a service, but to keep connected, to engage people; to nurture relationships.

However, when called on to characterise their institutions, some museum directors continue to fall back on problematic concepts. Australian Museum Director and CEO Kim McKay argues museums are ‘safe places for unsafe ideas’ and provide platforms for difficult conversations. Safe for who? Which relationships are we prioritising here? Whose voices are featured, and who feels they have the right and the opportunity to contribute to the conversation?

Western Australian Museum CEO Alec Coles aligns with McKay: ‘Museums are places that people tend to trust, where you can have some of these difficult conversations without the rancour and bias that you see elsewhere.’ The OED defines rancour as ‘a deep-rooted and bitter ill feeling; resentment or animosity, esp. of long standing.’ If a state museum in a settler-colonial country is intent on avoiding conversations that include long-standing feelings of resentment and animosity, think about who that might exclude. As for the claim that museums are free from bias or above politics rather than embedded in and complicit with complex networks of power and influence, the sooner we leave behind this persistent falsehood the better.

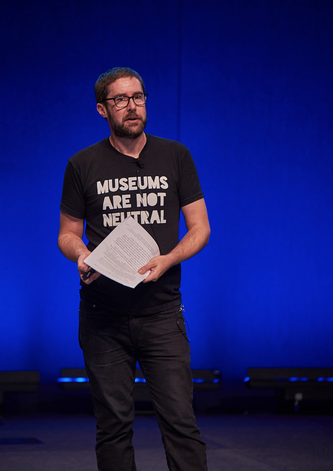

T-shirt from Museums Are Not Neutral.

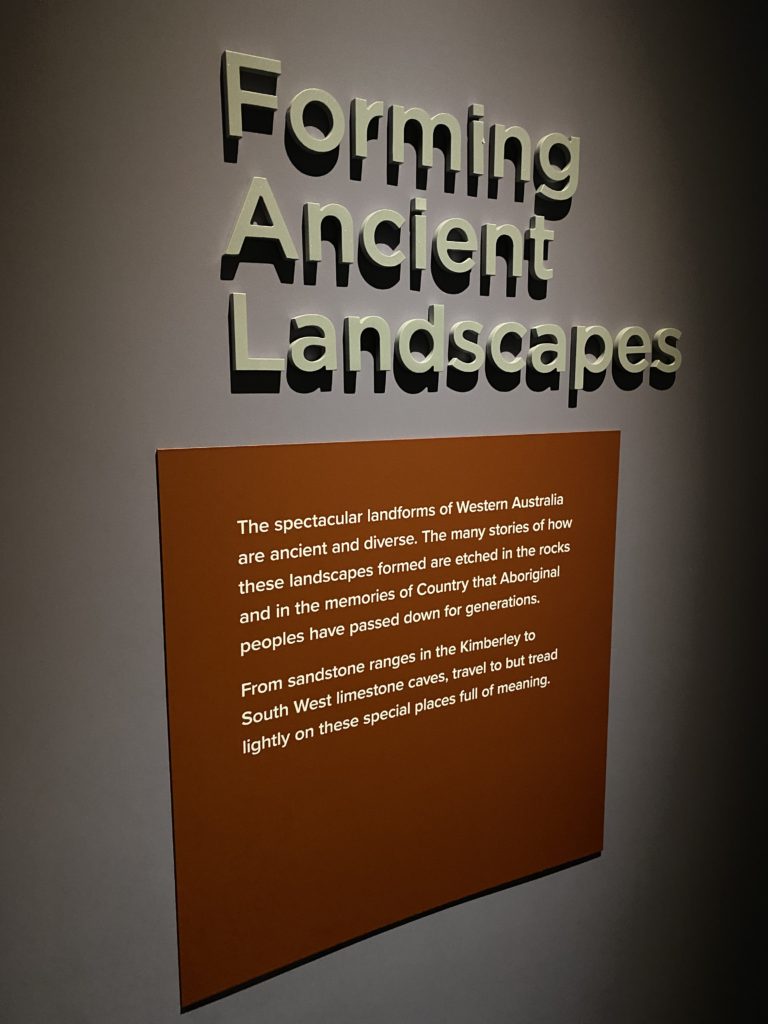

Which is not to criticise the WA Museum Boola Bardip overall. Walk into the redeveloped museum and you’ll find some beautiful examples of contemporary curatorship and exhibitions design where First Nations ideas and knowledge are woven through not just the Indigenous galleries, but history, natural history, and science galleries too. There are evocative text panels like this one, titled ‘Forming Ancient Landscapes.’

It concludes by urging us to ‘tread lightly on these special places full of meaning.’

There’s also a Rio Tinto Gallery.

A cave in Western Australia’s Juukan Gorge, with evidence of continuous occupation dating back 46,000 years, was permanently destroyed by Rio Tinto in May 2020 to expand an iron ore mine. WA Museum Boola Bardip opened in November 2020. Whatever the institution’s strengths, in pursuit of a ‘lack of bias’ accountability to particular relations has become blurred, and ethical discussions pushed outside the museum, to be dominated by oppositional arguments about property and ownership, cultural versus legal rights, and monetary profit versus cultural heritage.

Though a much more complex path to take, prioritising certain relationships and making ourselves accountable to those, and enacting an ethics of care where we pay heed to important relationships and the need to nurture these over time, could lead to quite different decisions. These decisions may come at a financial cost, but stepping back from making them is to pretend that we are not already part of these networks, and people will already hold us accountable. As they should.

Accountability does not mean retreating into the safety of considering the ’general public’. That path leads back to claims of neutrality, objectivity, and universal truths. Claims that the museum is neutral and safe by its nature. Claims that preserve existing hierarchies, shore up privilege, and entrench inequality.

As we (hopefully) emerge from the past few years, I believe we have not just an opportunity, but a responsibility to actively nurture other paths and other possibilities. So who do we want to be accountable to? The Traditional Land Owners we collaborate with and on whose unceded lands we live and work, or Rio Tinto so they can fund the refurbishment of a gallery space? Trans kids, or conservative religious lobby groups and rightwing media scaremongers? ‘Right to life’ activists (who, as someone pointed out recently, should actually be called proponents of forced birth) or those who support bodily autonomy? Fossil fuel interests, or the environment?

We can’t be equally accountable to all of them, and any claim a museum should ‘not take sides’ or must be free from bias will almost inevitably fail to support social, cultural, and economic progress. So which of our relations will we be accountable to? The future of our institutions will be shaped by our answers to these questions, in challenging ways, but also in exciting, refreshing, and invigorating ways.

There will inevitably be resistance to this idea. Gilligan talks about the difference between hierarchies, where power is vested in a small number of people at the top, and networks where power resides in the richly-interconnected ‘centre.’ Moving from one to the other means the top of the hierarchy becomes more precarious and vulnerable, on the edge of a delicate web.

Relational networks are also more complex structures to manage, and are more clearly differentiated across institutions rather than being predictable and readily universalised. These are context-specific spaces composed of parts that can be difficult to replace, quickly restructure, or discard.

But embracing a more relational approach can also be an immensely rewarding way of working—an approach that, as Donna Haraway writes, will allow us ‘to make trouble, to stir up potent responses to devastating events, as well as to settle troubled waters and rebuild quiet places.’

The most compelling example of this I have seen in recent times was Unsettled at the Australian Museum. Curated by Laura McBride and Dr Mariko Smith, Unsettled was filled with potent responses to devastating events, as well as providing quiet places for reflection and contemplation. It was clear throughout that the team involved had embraced the idea of accountability. While evident that a range of visitors and audiences had been considered—this was an exhibition that had done its research, knew the statistics, and cited its sources for those who wanted to check—relationships with First Nations peoples and communities were prioritised. The curators held themselves accountable to particular relationships, many of which lay outside the institution for which they worked, and did so in a way that was productive and powerful rather than treating accountability as a constraint.

If we want to focus on the future of museums, we can focus on beautiful artworks, iconic objects, amazing specimens, and engaging experiences; we can focus on new buildings and developments (some of which are genuinely exciting); we can focus on new technologies and digital engagement opportunities. But we are creating little more than physical and virtual spaces filled with bric-a-brac if we do not develop and nurture ethical relationships.

As we deal with the disruptions of the past few years, it’s time to nurture the relationships that count. And to make ourselves accountable to them.

Leave a Reply